By Columbia University January 30, 2026

Collected at: https://scitechdaily.com/physicists-watch-a-superfluid-freeze-revealing-a-strange-new-quantum-state-of-matter/

Physicists have observed a strange new quantum phase in a graphene-based system, where a superfluid appears to freeze into a solid-like state.

Cooling usually pushes matter through a simple sequence. A gas condenses into a liquid, and with further cooling the liquid locks into a solid. Helium helped reveal that the quantum world can take a very different route. In the early 20th century, researchers found that helium, when chilled to extreme temperatures, can enter a superfluid state. In that form, it can move without dissipating energy and shows other counterintuitive behaviors, including creeping up and out of containers.

That discovery left physicists with an even more intriguing puzzle: if a superfluid is cooled further still, does it settle into a new phase, or does “frictionless motion” remain the end of the story? Scientists have been chasing that answer for about fifty years.

A Superfluid That Stops Moving

A report in Nature now points to a striking outcome. A team led by Cory Dean at Columbia University and Jia Li at the University of Texas at Austin observed a superfluid that did something it is not supposed to do in the simplest picture: it stopped.

“For the first time, we’ve seen a superfluid undergo a phase transition to become what appears to be a supersolid,” said Dean. It’s like water freezing to ice, but at the quantum level.

The idea of a supersolid sounds like a contradiction because it blends two identities. A classical solid is defined by atoms arranged in a fixed, repeating crystal lattice. A superfluid, by contrast, is known for its ability to flow without resistance. Supersolids are predicted to combine both traits, meaning the material would be crystal-like in its internal order while still retaining the hallmark frictionless flow associated with superfluidity.

The Long Search for Supersolids

For all the theory and debate, the most famous candidate, helium, has not provided a definitive, natural example of a superfluid turning into a supersolid. Researchers have built supersolid-like systems in the atomic, molecular, and optical (AMO) sub-branch of physics, but those demonstrations typically rely on lasers and optical components to impose a repeating structure. This creates what is known as a periodic trap that encourages the fluid into a crystal-like pattern, a bit like Jello confined in an ice cube tray.

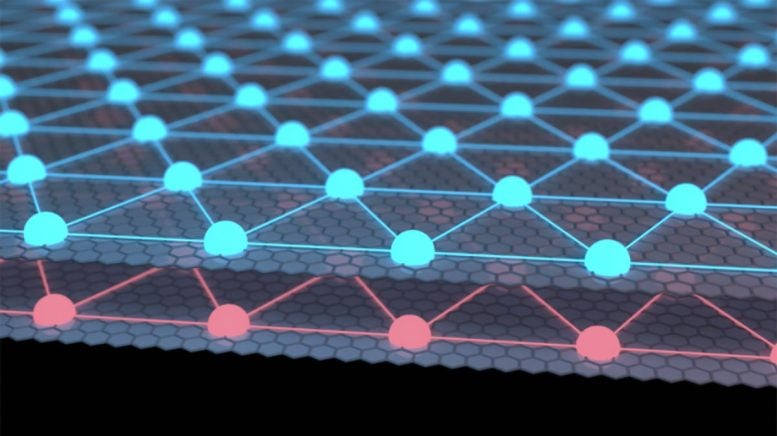

What remained missing was a case where a supersolid emerges without that kind of externally imposed pattern, a gap that helped sustain one of the major controversies in condensed matter physics. Dean’s group tackled that challenge by shifting from helium to graphene, a material that is already a crystal in its own right—a sheet of carbon atoms just one atom thick. The team included Li during his time as a postdoc at Columbia and a former PhD student, Yihang Zeng (now an assistant professor at Purdue University).

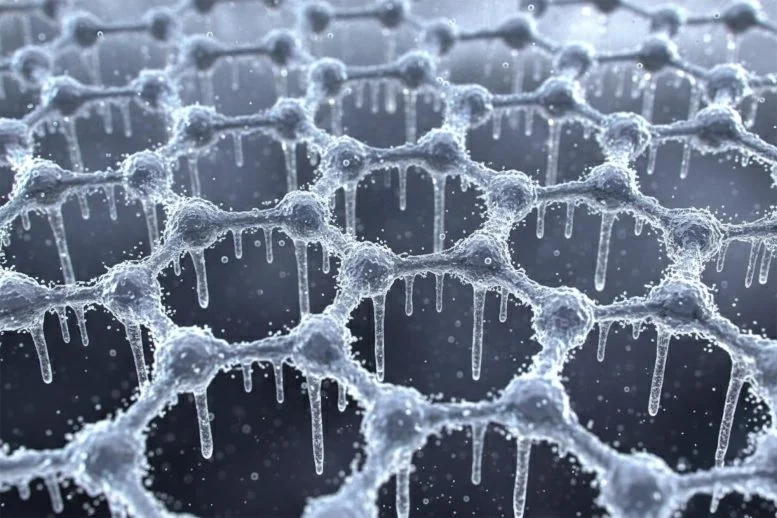

Graphene can host what are known as excitons. These quasiparticles form when two-atom-thin sheets of graphene are layered together and manipulated such that one layer has extra electrons and the other, extra holes (which are left behind when electrons leave the layer in response to light). Negatively charged electrons and positively charged holes can combine into excitons. Add a strong magnetic field, and excitons can form a superfluid.

A Reversed Phase Transition

2D materials like graphene have emerged as promising platforms to explore and manipulate phenomena like superfluidity and superconductivity. That’s because there are a number of different “knobs” researchers can adjust, like temperature, electromagnetic fields, and even the distance between the layers, to fine-tune their properties.

When Dean’s team began turning the knobs to control the excitons in their samples, they saw an unexpected relationship between the density of the quasiparticles and temperature. At high density, their excitons behaved like a superfluid, but as their density decreased, they stopped moving and became insulators. When the team increased the temperature, superfluidity returned.

“Superfluidity is generally regarded as the low-temperature ground state,” said Li. “Observing an insulating phase that melts into a superfluid is unprecedented. This strongly suggests that the low-temperature phase is a highly unusual exciton solid.”

Is It Really a Supersolid?

So, is it a supersolid? “We are left to speculate some, as our ability to interrogate insulators stops a little,” explained Dean—their expertise is in transport measurements, and insulators don’t transport a current. “For now, we’re exploring the boundaries around this insulating state, while building new tools to measure it directly.”

They are also looking at other layered materials. The excitonic superfluid, and likely supersolid, that forms in bilayer graphene only does so with the help of a strong magnetic field. Alternatives are somewhat more challenging to fabricate into the necessary arrangements, but they could stabilize the quasiparticles at even higher temperatures and without the need for a magnet.

Controlling a superfluid in a 2D material is an exciting prospect—compared to helium, for example, excitons are thousands of times lighter, so they could potentially form quantum states such as superfluids and supersolids at much higher temperatures. The future of supersolids remains to be realized, but there is now solid evidence that 2D materials will help researchers understand this enigmatic quantum phase.

Reference: “Observation of a superfluid-to-insulator transition of bilayer excitons” by Yihang Zeng, Dihao Sun, Naiyuan J. Zhang, Ron Q. Nguyen, Qianhui Shi, A. Okounkova, K. Watanabe, T. Taniguchi, J. Hone, C. R. Dean and J. I. A. Li, 28 January 2026, Nature.

DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-09986-w

Funding: US Department of Energy, U.S. National Science Foundation, Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, Air Force Office of Scientific Research, National High Magnetic Field Laboratory

Leave a Reply