By Matthew Williams – December 04, 2025

Collected at: https://www.universetoday.com/articles/new-research-could-explain-why-earth-has-active-tectonics-and-venus-does-not

Plate tectonics is a fundamental aspect of Earth’s geological activity and history. In addition to constantly rearranging the placement of continents, they also play a major role in maintaining the conditions that ensure Earth’s continued habitability. However, Earth is the only terrestrial (rocky) planet in the Solar System with active plate tectonics. While this is understandable for Mercury and Mars, which are single-plate planets that are largely geologically inactive, due to rapid cooling in their interiors billions of years ago. But Venus, Earth’s “Sister Planet,” has remained something of a mystery.

To date, planetary scientists have been unable to deduce why Venus is geologically inactive compared to Earth. However, an international team recently made a significant breakthrough in our understanding of terrestrial planets and their tectonic evolution. Led by researchers from the University of Hong Kong, the team used advanced numerical models to identify six distinct regimes for planetary tectonics. Their research provides a new framework for classifying the range of planetary tectonics and tools for future planetary exploration.

The team was led by postdoctoral fellow Dr. Tianyang Lyu, along with Professor Man Hoi Lee and Professor Guochun Zhao of the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences at The University of Hong Kong (HKU). They were joined by Prof. Maxim D. Ballmer from the University College London (UCL), Dr. Yun Jan from the Freie Universität Berlin, Prof. Zhong-Hai Li of the State Key Laboratory of Earth System Numerical Modeling and Application, and Prof. Benjen Wu of Nanjing University. The paper describing their research and findings has been published in Nature Communications.

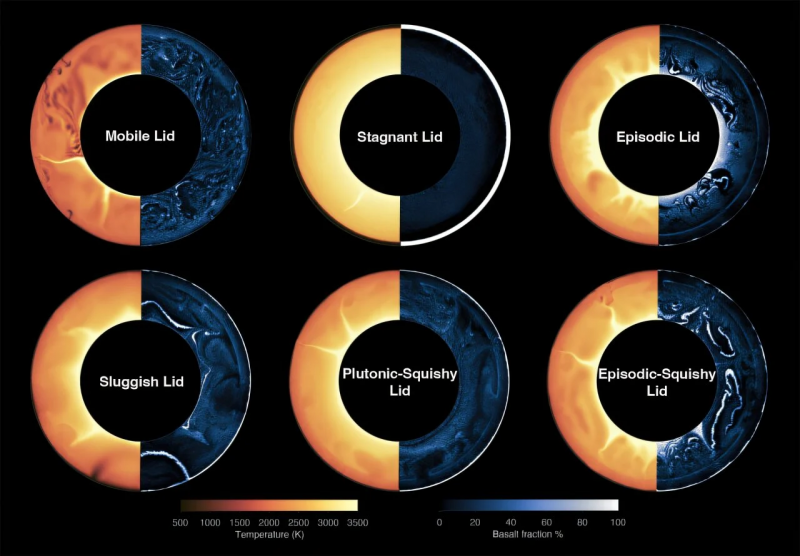

Snapshots of the six tectonic regimes identified by the research team. Credit: Lyu, et al. (2025).

Tectonic regimes describe the large-scale deformation of a planet’s surface and the processes that drive it. These regimes are responsible for shaping a planet’s geological activity, internal evolution, magnetic field, and atmospheric composition – all of which play a huge role in planetary habitability. For example, the endless cycling of Earth’s lithosphere (the crust and upper mantle) is integral to the planet’s carbon cycle, including volcanic activity and the sequestration of carbon in carbonate rocks. This has ensured that the level of carbon dioxide (a major greenhouse gas) in our atmosphere has remained stable over time.

Meanwhile, Earth’s intrinsic magnetic field is driven by dynamo action in the core, where the molten outer core counter-rotates with the planet’s solid inner core. This field prevents most cosmic rays that interact with Earth’s upper atmosphere from reaching the surface, where they would cause significant harm to living beings. One of the most enduring mysteries in planetary science is why Earth experiences plate tectonics while Venus does not. Given that Venus is comparable in size, mass, and density to Earth, the same mechanism that arrested geological activity on Mars and Mercury should not apply.

Earth’s plate tectonic activity is characterized by a “mobile lid” regime, marked by ridges, faults, and subduction zones. The constant cycling of Earth’s lithosphere, where ridges are pushed up, and subduction zones send material downward, is much like a conveyor belt that constantly refreshes Earth’s surface. For planets that do not experience tectonic activity, craters and other features are preserved for eons or longer. In previous studies, researchers have proposed additional tectonic regimes, such as “sluggish lid” or “plutonic-squishy lid.”

But how these regimes relate to each other and terrestrial planets in general has remained unclear to geologists. Addressing this question, Lyu and his team conducted a statistical analysis of mantle convection models to produce a list of possible tectonic regimes. As Dr. Lyu explained in a HKU press release:

Through statistical analysis of vast amounts of model data, we were able to identify six tectonic regimes for the first time quantitatively. These include the mobile lid (like modern Earth), the stagnant lid (like Mars), and our newly discovered ‘episodic-squishy lid.’ This new regime is characterized by an alternation between two modes of activity, offering a fresh perspective on how planets transition from an inactive to an active state.

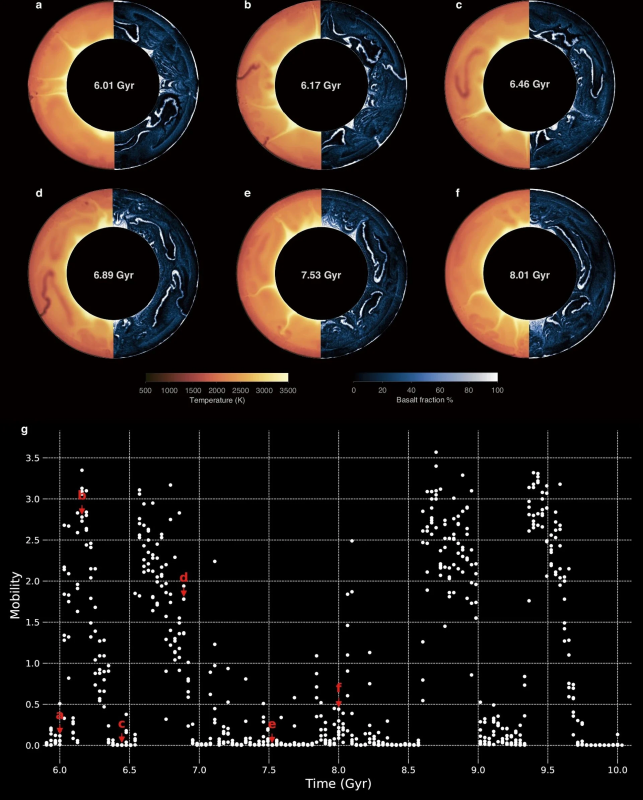

Model evolution and mobility dynamics of the Episodic-Squishy Lid regime. Credit: Lyu, et al. (2025).

A major challenge in the study of geological activity is hysteresis (or “memory effect”), a phenomenon in which a planet’s tectonic state depends largely on its past, not just its present, activity. To overcome this, the team also developed a comprehensive diagram that accounted for how all six regimes could transition from one to another as terrestrial planets cool. This revealed that the pathways for tectonic evolution are surprisingly predictable, especially when lithospheres weaken over time. According to geological records, this is what happened here on Earth.

As the lithosphere cooled, it became more prone to fracturing, leading to the formation of plates and Earth’s current tectonic state. Since this activity was crucial to maintaining conditions favorable to life as we know it, these results provide a vital clue about how and when Earth became a habitable planet. In addition, it offers a compelling explanation for Venus’ geology, which is highly consistent with the “plutonic-squishy lid” or “episodic-squishy lid” regimes identified in their model. In these regimes, lithospheres are weakened by rising magma, leading to regional, intermittent volcanic activity rather than global-mantle-driven processes.

This presents another interesting takeaway of the team’s research, which could provide insight into the decades-long debate over volcanism on Venus. Whereas planetary scientists once believed that Venus was geologically dead, recent findings have challenged that view by suggesting the presence of active volcanoes. This study supports these findings by indicating that volcanism could persist despite the absence of tectonic plate activity. In essence, the team’s results provide a theoretical reference and potential observation sites for future missions to Venus. As Dr. Ballmer noted:

Our models intimately link mantle convection with magmatic activity. This allows us to view the long geological history of Earth and the current state of Venus within a unified theoretical framework, and it provides a crucial theoretical basis for the search for potentially habitable Earth analogs and super-Earths outside our solar system.

Further Reading: Hong Kong University, Nature

Leave a Reply