December 3, 2025 by Noah Lloyd, Northeastern University

Collected at: https://phys.org/news/2025-12-machine-england.html

New England’s a complicated place, especially when it comes to flooding.

Samuel Muñoz, associate professor of marine and environmental sciences at Northeastern University, says that the region’s complex network of small, interconnecting rivers, a diverse topography and Atlantic atmospheric movements all make it extremely difficult to model mathematically.

New research from Muñoz and Ph.D. student Lindsay Lawrence published in Geophysical Research Letters uses machine learning to build “self-organizing maps” to reveal how atmospheric and land conditions interact, identifying four patterns that lead to flooding in New England. This breakthrough in weather modeling promises to help predict floods before they happen, especially in a warming climate.

The complexity

Muñoz says that his previous flooding research focused on big rivers, like the Mississippi. “In some of the other systems that we work in, the mechanisms that cause floods are not simple, but simpler” than in New England, he says, where the topography is more complex, there are smaller but more numerous rivers, and then there’s the rain.

New England can get precipitation in a lot of ways, he says, from snow to the occasional hurricane.

Lawrence notes that rain itself is tremendously difficult to model, one reason why weather apps are never quite as accurate as you might like. The “nerdy answer,” she says, as to why precipitation is so tricky, is that “the actual microphysics of clouds is really, really incredibly difficult.”

Muñoz says that it’s also a question of scale. Our current weather models divide the world into grids with cells that are 100 kilometers to a side, about 62 miles. The size of these grids means that the models are good at predicting things like pressure and temperature, but the actual mechanics of condensation, and the resulting precipitation, occur at a much smaller scale.

Machine learning has helped them overcome this problem.

Muñoz says that while New England is a complex region to model meteorologically the self-organizing maps created with Lawrence will help predict flooding events not only in the near term, but also as the atmosphere changes due to a warming climate. Credit: Alyssa Stone/Northeastern University

The maps

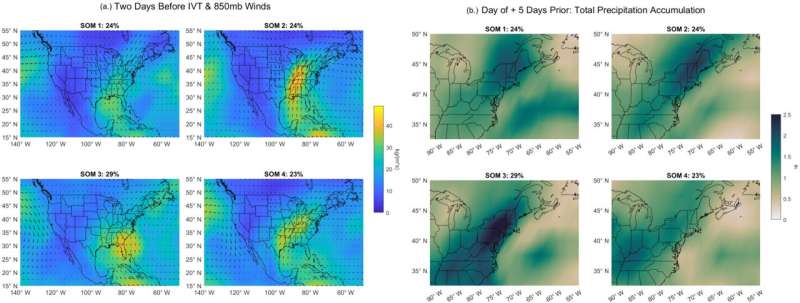

By aggregating data from 1979 on, Lawrence developed so-called self-organizing maps to condense data down into modelable groups and clusters.

Self-organizing maps, and the machine learning protocol involved in creating them, have been in use since the 1980s, Lawrence notes. They’re called maps, she continues, because while reducing the data, they preserve “what’s called the topology, the shape of the data, the characteristics of the data and grouping features.”

Lawrence and Muñoz were interested in grouping similar events: floods. And once Lawrence’s maps were in place, she could identify four concrete patterns of pressure, temperature and surface conditions, like soil moisture, that contribute to flooding.

Lawrence says that the maps also demonstrate seasonality, when they are most likely to occur. Three of the maps trend toward the later winter or early spring, while one is more characteristic of the summer. And since there is a noticeable pattern of pressure events and soil moisture in each of the maps, she says, meteorologists can use them to issue earlier warnings and save lives.

What comes next

Muñoz notes that they were also motivated to think about climate change and how it will impact future river flows, floods and droughts in the region.

That has historically been a struggle because of how Earth models struggle with precipitation. However, he continues, tying “flood events to patterns of pressure and temperature” and soil moisture, “will let us look at how those conditions change over time as we change the composition of the atmosphere” through global warming.

More information: L. Lawrence et al, Connecting Large‐Scale Atmospheric and Land Surface Patterns to New England Riverine Peak Flow Events, Geophysical Research Letters (2025). DOI: 10.1029/2025gl116899

Journal information: Geophysical Research Letters

Leave a Reply