By University of Basel November 26, 2025

Collected at: https://scitechdaily.com/physicists-rewrite-thermodynamics-for-the-quantum-age/

Researchers have devised a new way to define thermodynamic concepts in microscopic quantum systems, where conventional distinctions between heat and work begin to blur.

Researchers at the University of Basel have introduced a new way to apply thermodynamic principles to very small quantum systems.

The story of thermodynamics traces back to 1798, when officer and physicist Benjamin Thompson (a.k.a. Count Rumford) studied the drilling of cannon barrels in Munich and realized that heat is not a physical substance but can be produced endlessly through mechanical friction.

To explore this idea, Rumford placed the heated barrels in water and timed how long it took for the water to boil. Experiments like these eventually helped shape the field of thermodynamics in the 19th century, a period when the discipline played a key role in the Industrial Revolution by revealing how heat could be converted into useful work in devices such as steam engines.

Today, the major laws of thermodynamics form essential knowledge across the natural sciences. They state that the total energy, which includes both heat and work, remains constant in a closed system, and that entropy, which represents disorder, cannot decrease.

These laws are generally valid, but when trying to apply them to the smallest quantum systems, one quickly runs into difficulties. A team of researchers at the University of Basel, led by Professor Patrick Potts, has now found a new way to define thermodynamic quantities consistently for certain quantum systems. Their results were recently published in the scientific journal Physical Review Letters.

Laser light in a cavity

“The problem we have with the thermodynamic description of quantum systems is that in such systems, everything is microscopic. This means that the distinction between work, which is useful macroscopic energy, and heat, or disordered microscopic motion, is no longer straightforward”, doctoral student Aaron Daniel explains.

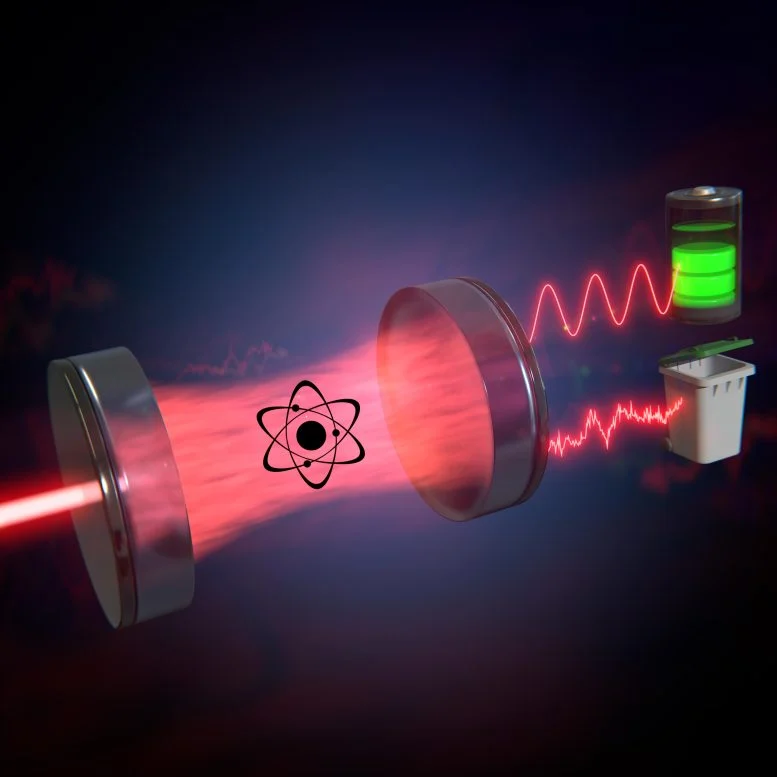

By way of an example, Daniel and his colleagues took a closer look at so-called cavity resonators in which incident laser light is reflected back and forth between two mirrors and, eventually, partially exits the cavity.

Unlike the light from an ordinary light bulb or LED, laser light has the special property that all its electromagnetic waves oscillate exactly in lockstep. However, if the laser light passes through a cavity filled with atoms, this lockstep – also called coherence – can be disturbed to a greater or lesser extent. In this case, the light becomes partially or entirely incoherent (which corresponds to the disordered motion of particles). “The coherence of the light in such a laser-cavity-system was the starting point of our calculations,” says Max Schrauwen, a bachelor’s student involved in the project.

Work by coherence

The researchers first defined what they mean by “work” in the context of laser light: for instance, the capacity to charge a so-called quantum battery. This requires coherent light that can collectively take an ensemble of atoms to an excited state. For the sake of simplicity, one might now assume that the coherent laser light entering the cavity is able to do work, while the partially incoherent laser light exiting the cavity is not. In this view, the light leaving the cavity should be called “heat.”

However, even partially incoherent light can, in principle, still do some useful work – just less than completely coherent light. Daniel and his colleagues investigated what happens when the coherent part of the exiting light is considered work and only the incoherent part is treated as heat. The result: if work is defined in this way, both laws of thermodynamics are fulfilled and, therefore, the approach is consistent.

“In the future, we can use our formalism to consider more subtle problems in quantum thermodynamics,” says Daniel. This is relevant, for instance, for applications in quantum technologies such as quantum networks. Furthermore, the transition from classical to quantum behavior of macroscopic systems can be investigated even better in this way.

Reference: “Thermodynamic Framework for Coherently Driven Systems” by Max Schrauwen, Aaron Daniel, Marcelo Janovitch and Patrick P. Potts, 24 November 2025, Physical Review Letters.

DOI: 10.1103/zdbv-rksc

Leave a Reply