November 28, 2025 by Ingrid Fadelli, Phys.org

Collected at: https://phys.org/news/2025-11-quantum-sensor-based-silicon-carbide.html

Over the past decades, physicists and quantum engineers introduced a wide range of systems that perform desired functions leveraging quantum mechanical effects. These include so-called quantum sensors, devices that rely on qubits (i.e., units of quantum information) to detect weak magnetic or electric fields.

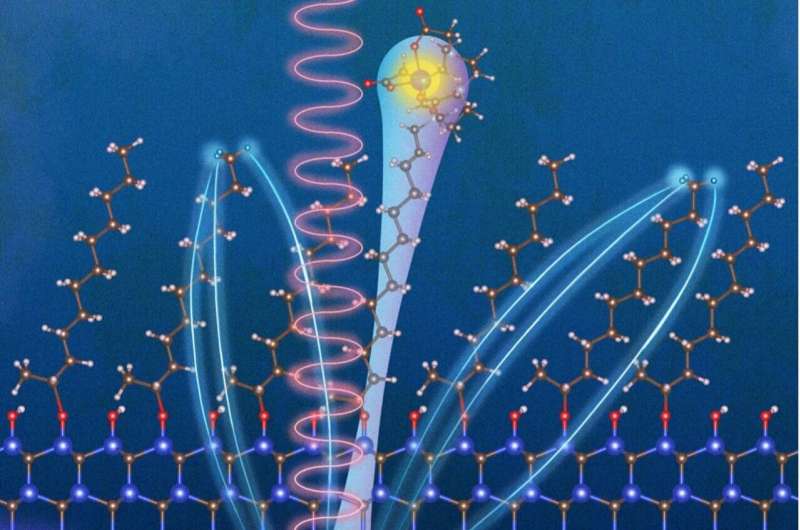

Researchers at the HUN-REN Wigner Research Center for Physics, the Beijing Computational Science Research Center, the University of Science and Technology of China and other institutes recently introduced a new quantum sensing platform that utilizes silicon carbide (SiC)-based spin qubits, which store quantum information in the inherent angular momentum of electrons. This system, introduced in a paper published in Nature Materials, operates at room temperature and measures qubit signals using near-infrared light.

“Our project began with a puzzle,” Adam Gali, senior author of the paper told Phys.org. “Quantum defects that sit just a few nanometers below a surface are supposed to be fantastic sensors—but in practice, they pick up a lot of ‘junk’ signals from the surface itself. This is especially true in SiC. Its standard oxide surface is full of stray charges and spins, and those produce noise that overwhelms the quantum defects we actually want to use for sensing. We wanted to break out of this limitation.”

Instead of developing techniques or strategies to reduce the noise in conventional SiC surfaces, Gali and his colleagues tried to design an entirely new surface. This ultimately became the primary motivation behind their study.

“Our goal was to create a clean, stable, bio-friendly SiC surface that doesn’t generate noise, so that the shallow quantum defects beneath it can finally do what they are good at—detecting external signals with clarity, even at room temperature,” said Gali.

“In short, the project grew from a simple realization: if we give these quantum defects a much quieter environment, they suddenly become powerful, practical sensors.”

A system based on non-invasive silicon carbide qubits

The quantum sensor introduced by the researchers was built by carefully engineering defects known as ‘divacancies’ and ‘divacancy-like species’ in 4H-SiC structures. In their system, these defects behave like tiny quantum spins, which can be controlled using lasers and microwaves.

“As they sit only a few nanometers beneath the surface, they are extremely sensitive to magnetic and chemical signals coming from whatever is placed on top—such as molecules or biological samples,” explained Gali. “The real breakthrough is the surface we engineered.”

In most materials previously used to develop quantum sensors, shallow quantum defects are overwhelmed by the noise that originates from unwanted charges and spins on the surface of materials. To solve this problem, Gali and his colleagues created an entirely new, bio-inert surface that significantly suppresses these noisy interface states.

“With the surface quieted down, the quantum spins can finally operate cleanly and detect external signals with high precision,” said Gali.

“Another advantage is that SiC defects naturally emit light in the near-infrared range, a range that penetrates biological materials and liquids well. Combined with our stable, chemically inert surface, this means the sensor works reliably at room temperature and in biological or aqueous environments, opening the door to practical quantum sensing in realistic conditions.”

Initial results and future possibilities

In initial tests, the new surface engineered by the authors attained highly promising results, producing significantly less noise and thus enhancing the stability of qubits. This recent work thus highlights the impact of a material’s chemistry on the performance of quantum technologies, showing that carefully engineered quantum defects can significantly reduce the noise originating from surface states.

“By replacing the usual oxide with an alkene-terminated SiC surface, we were able to suppress the noisy interface defects that normally drown out the quantum signal,” said Gali. “This allowed us to recover clean, high-fidelity spin readout from defects located just a few nanometers below the surface—something that has not been possible on conventional oxidized SiC.”

Notably, the researchers showed that shallow defects on their newly introduced surface can also implement stable spin sensing protocols at room temperatures and in environments that would typically be considered too noisy or chemically reactive. Their surface engineering strategy thus did not only improve signals in their system, but also transformed SiC into a viable platform for realizing quantum sensing on the nanoscale.

“These advances open up a wide range of applications,” said Gali. “The sensor could be used for nanoscale magnetic field detection, surface NMR of tiny molecular samples, and probing chemical or biological processes in real time.”

Two key advantages of the team’s surface are its bio-inertness (i.e., compatibility with living tissues and biological systems) and its ability to emit near-infrared light. In the future, sensors based on the surface could thus be used to create bio-compatible quantum sensing devices that can be safely implanted inside the body or be deployed in environments that are filled with reactive chemicals.

“Looking ahead, we want to push the capabilities of this platform even further. One direction is to improve how we create shallow quantum defects, so that their depth, density and charge state can be controlled with even greater precision,” said Gali.

“In parallel, we plan to refine the surface chemistry, making it easier to attach specific biological or chemical targets directly to the sensor in a controlled and stable way.”

The researchers are now planning to further improve the surface they engineered. For instance, they are working on an upgraded version of their surface that is based on isotopically purified SiC, a cleaner form of SiC that could extend the coherence time of spins in their system, boosting its sensitivity.

“With these improvements in place, our next goal is to move from demonstrations to real sensing experiments: detecting paramagnetic molecules, performing nanoscale NMR on surface-bound samples, and eventually exploring biological or chemical processes in realistic environments,” added Gali.

“In short, we are working toward turning this system into a versatile, room-temperature quantum sensing tool for chemistry, biology and materials science.”

More information: Pei Li et al, Non-invasive bioinert room-temperature quantum sensor from silicon carbide qubits, Nature Materials (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41563-025-02382-9.

Journal information: Nature Materials

Leave a Reply