November 21, 2025 by David Appell, Phys.org

Collected at: https://phys.org/news/2025-11-experimental-result-muon-theorists.html

For experimental physicists, the latest measurement of the muon is the best of times. For theorists there’s still work to do.

Colliding 300 billion muons over four years at the Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory in the U.S., the Muon g-2 Collaboration—a group of over 200 researchers—has measured the magnetic strength of the muon to unprecedented precision: accurate to 127 parts per billion.

These final results on the muon’s magnetic moment—measured by its frequency of the moment’s wobbling in an external magnetic field—are the end of a chain of experimental efforts going back 30 years and have been published in the journal Physical Review Letters.

Theoretical background and quantum corrections

The muon is the heavier sibling of the electron, with a mass about 207 times higher but unstable, with an average lifetime of 2.2 microseconds. It has the same spin of ½ (times the reduced Planck’s constant). So, the muon’s classical magnetic moment, a measure of how its spin acts like a bar magnet and behaves in a magnetic field, should be the same as the electron’s—before quantum field theory is taken into account. That was the beginning of this story, first with the electron, with the initial hero being the American physicist Julian Schwinger.

Dirac’s theory, which combines Schrödinger quantum mechanics with special relativity, predicts a spin magnetic moment of exactly one Bohr magneton. Physicists have come to categorize this using a dimensionless g-factor called the gyromagnetic ratio; Dirac’s equation predicts a value of 2 for it. (Schrödinger’s equation predicts zero, since there is no spin in the simplest version of quantum mechanics.)

Quantum field theory, which goes beyond Dirac’s theory and considers radiative corrections from very short-lived virtual particles in the field, predicts a slightly higher value, so the quantity g-2 that has come to be of interest.

Schwinger, a theoretical phenom who received his Ph.D. at 21 years of age, first predicted a value for the electron’s anomalous magnetic moment in 1948 when in a magnetic field, as determined by “radiative corrections” in his quantum field theory of electrodynamics: α/2π, where α is the fine structure constant approximately equal to 1/137. (Schwinger was so proud he had this equation engraved on his and his wife’s tombstone.)

The g-2 factor for the electron has now been calculated up to a tiny corrective factor of order α5 ≈ 2 x 10-11, which term requires 12,672 Feynman diagrams, some involving electroweak and strong force interactions. Most of these diagrams were calculated numerically; the leader behind this long-term project was the Japanese-born American physicist Toichiro Kinoshita.

Amazingly, the theoretical value agrees with the experiment to greater than 10 significant figures, and is the best prediction in all of science.

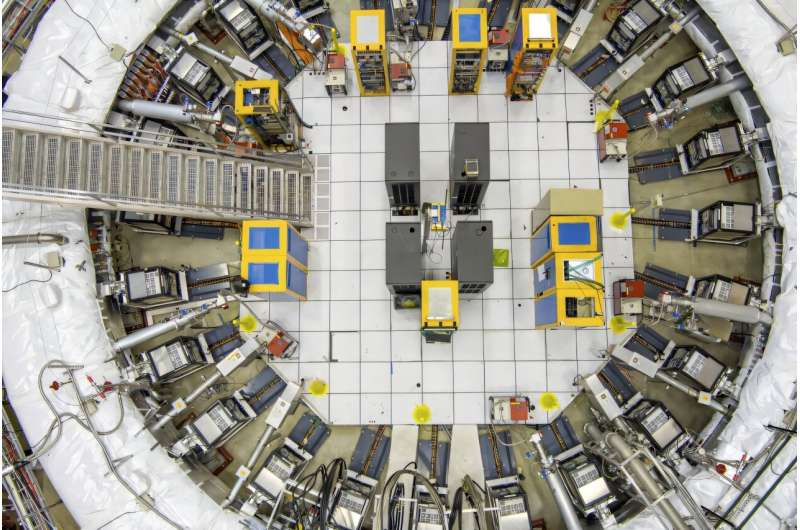

A bird’s-eye view of the Muon g-2 experiment at Fermi National Laboratory. Credit: R. Postel/Fermilab

Challenges in muon calculations and new initiatives

Much of the same was eventually done for the muon. Being more massive (and thus having more energy, according to Einstein’s equivalence of mass and energy), other interactions come increasingly into play beyond what the electron experiences: more interactions with the electroweak force and the strong force.

Especially troublesome, from a theoretical perspective, were virtual hadrons, composed of virtual particles comprised of two or more virtual quarks and of virtual gluons, bound together by the strong force. (In short, there is a lot more stuff flying all over the place.) In some parts of the calculation, experimental data from other particle collisions were used to evaluate sub-terms, such as electron-positron interactions. In other places, results from lattice gauge theory were utilized.

The Muon g-2 Theory Initiative was founded in 2016 to present the best prediction possible, which was published earlier this year, resolving differences between previous values from different groups. Within its inherent uncertainty, the prediction matches the recent experimental result, published by the Muon g-2 Collaboration.

Experimental achievements and ongoing questions

The laboratory result, containing 2.5 times the collisions of the previous best number, came from measuring the ratio of the precession frequencies for protons and muons and protons in Fermilab’s storage ring’s magnetic field, together with employing the most precise values of the fundamental constants. The result improved the global average of the muon’s g-2 by a factor of 4.

The theoretical and experimental values agree within 127 parts per billion; their error bars have an overlap. That’s like weighing a car wheel (tire and rim) to the nearest milligram. This is a triumph for the experimentalists. But some theorists had been hoping for a nonzero deviation to exist, perhaps indicating a need for new physics such as supersymmetry or other extensions of the Standard Model (SM) of particle physics such as axions, dark matter, extra dimensions or another Higgs boson.

“However, the uncertainty on the theoretical prediction is still four times larger than experiment,” Aida X. El-Khadra told Phys.org. El-Khadra is a professor of physics at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign and chair of the Muon g-2 Theory Initiative. The measurement “is a historic achievement that will not be challenged for years to come…” she said, and their prediction using the Standard Model does agree with experiment.

“This means that the question ‘Does the SM agree or disagree with the experimental value of the muon’s anomalous magnetic moment?’ is not yet satisfactorily answered,” she continued.

All the “drama,” she said, is “around the SM prediction is in hadronic vacuum polarization contribution,” meaning the contributions of virtual particles to the Standard Model’s contribution to the muon’s magnetic moment. She called their latest result a “dramatic” improvement from their 2020 result, because earlier lattice theory calculations from QCD (quantum chromodynamics, the theory of the strong force) were not yet mature enough. Her Initiative’s work will continue to reduce the final uncertainty.

Future prospects and the tau lepton challenge

Besides improvements on both the theory and experimental sides, a long-term goal is to do something similar for the even heavier cousin of the electron, the tau lepton. However there the problem is measuring the tau’s anomalous magnetic moment, since its decay lifetime is only 0.3 trillionths of a second, one-tenth of a million times shorter than the muon’s lifetime.

While the muon goes around the 45-meter circumference storage ring at Fermilab about 15 times before it decays, the tau would only travel about 100 micrometers.

More information: Anonymous, Measurement of the positive muon anomalous magnetic moment to 127 ppb, Physical Review Letters (2025). DOI: 10.1103/7clf-sm2v

Journal information: Physical Review Letters

Leave a Reply