By University of Arizona October 14, 2025

Collected at: https://scitechdaily.com/the-moons-deepest-scar-still-glows-with-clues-to-its-fiery-birth/

When NASA’s Artemis astronauts land near the moon’s south pole, they may be stepping into a region that holds vital clues to the moon’s ancient past.

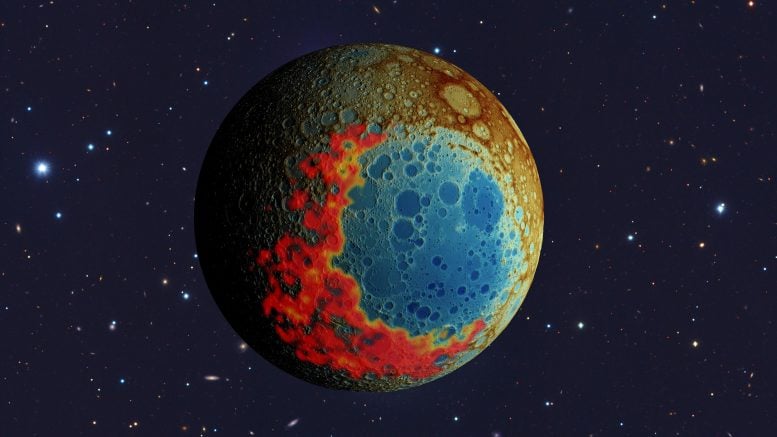

A new study reveals that a massive asteroid struck the moon from the north roughly 4.3 billion years ago, creating the enormous South Pole-Aitken Basin. This discovery overturns earlier theories about the impact’s direction and suggests that debris from deep within the moon’s interior still lies buried there.

Lunar Clues Await Artemis Astronauts

When astronauts arrive near the moon’s south pole as part of NASA’s upcoming Artemis missions, they may uncover a region rich with evidence about how the moon was formed. That possibility comes from new research led by Jeffrey Andrews-Hanna, a planetary scientist at the University of Arizona.

Published on October 8 in Nature, the study offers new insight into the moon’s turbulent origins and helps explain why its two sides look so different. The far side is heavily cratered, while the near side, familiar from Earth and home to the Apollo landing sites of the 1960s and 1970s, is far smoother and darker.

The Moon’s Violent Beginnings

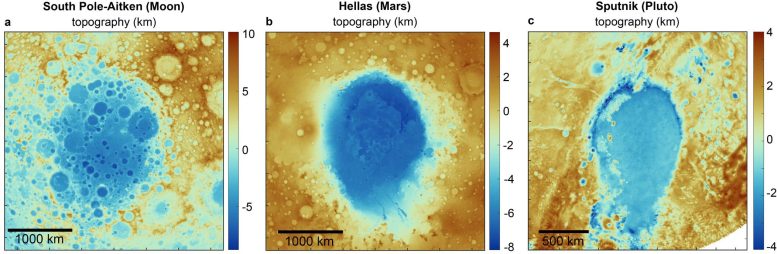

Around 4.3 billion years ago, when the solar system was still taking shape, a massive asteroid collided with the far side of the moon. The impact created the enormous South Pole-Aitken basin (SPA), the largest known crater on the lunar surface. Stretching roughly 1,200 miles from north to south and 1,000 miles from east to west, the basin’s elongated form suggests that the asteroid struck at an angle rather than in a direct hit.

Andrews-Hanna’s team compared SPA’s shape with other large impact sites found on planets and moons throughout the solar system. They discovered that these craters typically narrow in the direction the incoming object was traveling, creating an outline similar to a teardrop or an avocado.

Their findings overturn the long-held belief that the asteroid came from the south. Instead, the evidence indicates it approached from the north, since the basin becomes narrower toward the south. According to Andrews-Hanna, the southern, or “down-range,” end of the crater should contain thick layers of material thrown up from deep within the moon, while the northern, “up-range,” side should have much less of this buried debris.

The Best Place to Dig Deep

“This means that the Artemis missions will be landing on the down-range rim of the basin – the best place to study the largest and oldest impact basin on the moon, where most of the ejecta, material from deep within the moon’s interior, should be piled up,” he said.

In the paper, the group presents additional evidence supporting a southward impact from analyses of the topography, the thickness of the crust and the surface composition. In addition, the results offer new clues about on the interior structure of the moon and its evolution through time, according to the authors.

Ancient Clues Hidden in KREEP

It has long been thought that the early moon was melted by the energy released during its formation, creating a magma ocean covering the entire moon. As that magma ocean crystallized, heavy minerals sunk to make the lunar mantle, while light minerals floated to make the crust. However, some elements were excluded from the solid mantle and crust and instead became concentrated in the final liquids of the magma ocean. Those “leftover” elements included potassium, rare earth elements and phosphorus, collectively referred to as “KREEP ” – the acronym’s first letter reflecting potassium’s symbol in the periodic table of elements, “K.” According to Andrews-Hanna these elements were found to be particularly abundant on the moon’s near side.

“If you’ve ever left a can of soda in the freezer, you may have noticed that as the water becomes solid, the high fructose corn syrup resists freezing until the very end and instead becomes concentrated in the last bits of liquid,” he said. “We think something similar happened on the moon with KREEP.”

As it cooled over many millions of years, the magma ocean gradually solidified into crust and mantle. “And eventually you get to this point where you just have that tiny bit of liquid left sandwiched between the mantle and the crust, and that’s this KREEP-rich material,” he said.

Why the Near Side Got All the Action

“All of the KREEP-rich material and heat-producing elements somehow became concentrated on the moon’s near side, causing it to heat up and leading to intense volcanism that formed the dark volcanic plains that make for the familiar sight of the “face” of the Moon from Earth, according to Andrews-Hanna. However, the reason why the KREEP-rich material ended up on the nearside, and how that material evolved over time, has been a mystery.

The moon’s crust is much thicker on its far side than on its near side facing the Earth, an asymmetry that has scientists puzzled to this day. This asymmetry has affected all aspects of the moon’s evolution, including the latest stages of the magma ocean, Andrews-Hanna said.

“Our theory is that as the crust thickened on the far side, the magma ocean below was squeezed out to the sides, like toothpaste being squeezed out of a tube, until most of it ended up on the near side,” he said.

A Window Into the Moon’s Molten Past

The new study of the SPA impact crater revealed a striking and unexpected asymmetry around the basin that supports exactly that scenario: The ejecta blanket on its western side is rich in radioactive thorium, but not in its eastern flank. This suggests that the gash left by the impact created a window through the moon’s skin right at the boundary separating the crust underlain by the last remnants of the KREEP-enriched magma ocean from the “regular” crust.

“Our study shows that the distribution and composition of these materials match the predictions that we get by modeling the latest stages of the evolution of the magma ocean,” Andrews-Hanna said. “The last dregs of the lunar magma ocean ended up on the near side, where we see the highest concentrations of radioactive elements. But at some earlier time, a thin and patchy layer of magma ocean would have existed below parts of the far side, explaining the radioactive ejecta on one side of the SPA impact basin.”

Piecing Together the Moon’s Early History

Many mysteries surrounding the moon’s earliest history still remain, and once astronauts bring samples back to Earth, researchers hope to find more pieces to the puzzle. Remote sensing data collected by orbiting spacecraft like those used for this study provide researchers with a basic idea of the composition of the moon’s surface, according to Andrews-Hanna. Thorium, an important element in KREEP-rich material, is easy to spot, but getting a more detailed analysis of the composition is a heavier lift.

“Those samples will be analyzed by scientists around the world, including here at the University of Arizona, where we have state -of-the-art facilities that are specially designed for those types of analyses,” he said.

“With Artemis, we’ll have samples to study here on Earth, and we will know exactly what they are,” he said. “Our study shows that these samples may reveal even more about the early evolution of the moon than had been thought.”

Reference: “Southward impact excavated magma ocean at the lunar South Pole–Aitken basin” by Jeffrey C. Andrews-Hanna, William F. Bottke, Adrien Broquet, Alexander J. Evans, Gabriel Gowman, Brandon C. Johnson, James T. Keane, Janette N. Levin, Ananya Mallik, Simone Marchi, Samantha A. Moruzzi, Arkadeep Roy and Shigeru Wakita, 8 October 2025, Nature.

DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-09582-y

Leave a Reply