By The Hebrew University of Jerusalem July 20, 2025

Collected at: https://scitechdaily.com/this-blue-laser-just-solved-a-150-year-physics-mystery/

For over a century, physicists knew a strange magnetic signal should exist in everyday metals like copper and gold, but they couldn’t see it. Now, using only a blue laser and a clever tweak to a classic technique, scientists have detected this elusive phenomenon known as the optical Hall effect.

This breakthrough not only reveals hidden magnetic behaviors in materials once thought magnetically “silent,” but also hints at a new frontier in spin physics, quantum technologies, and electronics design—no wires or extreme conditions needed.

Shining Light on a Hidden Signal

A group of researchers has created an innovative way to detect extremely faint magnetic signals in everyday metals like copper, gold, and aluminum, using only light and a refined optical technique. Their findings, published in the journal Nature Communications, could lead to major advancements in technologies ranging from smartphones to quantum computing.

The Longstanding Puzzle: Why Can’t We See the Optical Hall Effect?

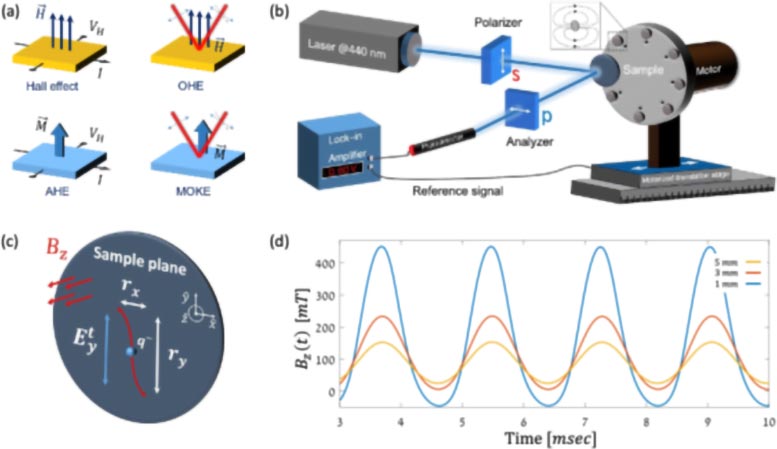

Scientists have long known that electric currents curve when exposed to magnetic fields. This behavior, called the Hall effect, is well documented in magnetic materials like iron. However, in metals that are not naturally magnetic, such as copper and gold, the effect is much weaker and more difficult to observe.

A similar but lesser-known phenomenon, known as the optical Hall effect, was predicted to provide insight into how electrons move when exposed to both light and magnetic fields. Yet despite more than a century of theoretical understanding, this effect has been too subtle to detect with visible light. Experts believed it existed, but no one had a method sensitive enough to confirm it.

“It was like trying to hear a whisper in a noisy room for decades,” said Prof. Amir Capua. “Everyone knew the whisper was there, but we didn’t have a microphone sensitive enough to hear it.”

Cracking the Code: A Closer Look at the Invisible

Led by Ph.D. candidate Nadav Am Shalom and Prof. Amir Capua from the Institute of Electrical Engineering and Applied Physics at Hebrew University, in collaboration with Prof. Binghai Yan from the Weizmann Institute of Science, Pennsylvania State University, and Prof. Igor Rozhansky from the University of Manchester, the study focuses on a tricky challenge in physics: how to detect tiny magnetic effects in materials that aren’t magnetic.

“You might think of metals like copper and gold as magnetically ‘quiet’—they don’t stick to your fridge like iron does,” explained Prof. Capua. “But in reality, under the right conditions, they do respond to magnetic fields—just in extremely subtle ways.”

The challenge has always been how to detect these tiny effects, especially using light in the visible spectrum where laser sources are readily available. Until now, the signal was simply too faint to observe.

Turning Up the Volume on Magnetic Whispers

To solve this, the researchers upgraded a method called the magneto-optical Kerr effect (MOKE), which uses a laser to measure how magnetism alters light’s reflection. Think of it like using a high-powered flashlight to catch the faintest glint off a surface in the dark.

By combining a 440-nanometer blue laser with large-amplitude modulation of the external magnetic field, they dramatically boosted the technique’s sensitivity. The result: they were able to pick up magnetic “echoes” in non-magnetic metals like copper, gold, aluminum, tantalum, and platinum—a feat previously considered near-impossible.

Why It Matters: When Noise Becomes a Signal

The Hall effect is a pivotal tool in the semiconductor industry and in studying materials at the atomic scale: it helps scientists figure out how many electrons are in a metal. But traditionally, measuring the Hall effect means physically attaching tiny wires to the device, a process that is time-consuming and tricky, especially when dealing with nanometer-sized components. The new approach, however, is much simpler: it merely requires to shine a laser on the elecrical device, no wires needed.

Digging deeper, the team found that what appeared to be random “noise” in their signal wasn’t random at all. Instead, it followed a clear pattern tied to a quantum property called spin-orbit coupling, which links how electrons move to how they spin—a key behavior in modern physics.

This connection also affects how magnetic energy dissipates in materials. These insights have direct implications for the design of magnetic memory, spintronic devices, and even quantum systems.

“It’s like discovering that static on a radio isn’t just interference—it’s someone whispering valuable information,” said Ph.D. candidate Am Shalom. “We’re now using light to ‘listen’ to these hidden messages from electrons.”

Looking Ahead: A New Window into Spin and Magnetism

The technique offers a non-invasive, highly sensitive tool for exploring magnetism in metals, without the need for massive magnets or cryogenic conditions. Its simplicity and precision could help engineers build faster processors, more energy-efficient systems, and sensors with unprecedented accuracy.

“This research turns a nearly 150-year-old scientific problem into a new opportunity,” said Prof. Capua.

“Interestingly, even Edwin Hall, the greatest scientists of all, who discovered the Hall effect, attempted to measure his effect using a beam of light with no success. He summarizes in the closing sentence of his notable paper from 1881: “I think that, if the action of silver had been one tenth as strong as that of iron, the effect would have been detected. No such effect was observed.” (E. Hall, 1881).”

“By tuning in to the right frequency—and knowing where to look—we’ve found a way to measure what was once thought invisible.”

Reference: “A sensitive MOKE and optical Hall effect technique at visible wavelengths: insights into the Gilbert damping” by Nadav Am-Shalom, Amit Rothschild, Nirel Bernstein, Michael Malka, Benjamin Assouline, Daniel Kaplan, Tobias Holder, Binghai Yan, Igor Rozhansky and Amir Capua, 17 July 2025, Nature Communications.

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-61249-4

Leave a Reply