By California Institute of Technology March 5, 2025

Collected at: https://scitechdaily.com/quantum-computings-biggest-problem-the-ocelot-chip-might-finally-solve-it/

Scientists are tackling one of the biggest hurdles in quantum computing: errors caused by noise and interference. Their solution? A new chip called Ocelot that uses “cat qubits” — a special type of qubit that dramatically reduces errors.

Traditional quantum systems require thousands of extra qubits for error correction, but this breakthrough could slash that number by 90%, bringing us closer to practical, powerful quantum computers m

Breaking Quantum Computing’s Biggest Barrier

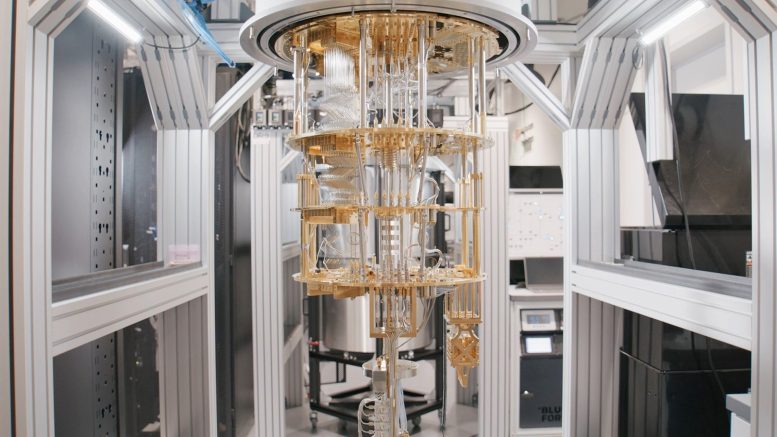

Scientists at the AWS Center for Quantum Computing, located on Caltech’s campus, have made significant progress in reducing errors in quantum computers — one of the biggest obstacles preventing these powerful machines from reaching their full potential.

Quantum computers operate using the strange principles of quantum mechanics, offering the potential to revolutionize fields like medicine, materials science, cryptography, and fundamental physics. However, while they have shown promise for specialized physics research, they remain too error-prone for more advanced, practical applications. Their extreme sensitivity to external disturbances — such as vibrations, heat, electromagnetic interference from everyday devices, and even cosmic rays — causes frequent errors, making them far less reliable than traditional computers.

A New Approach: Cat Qubits

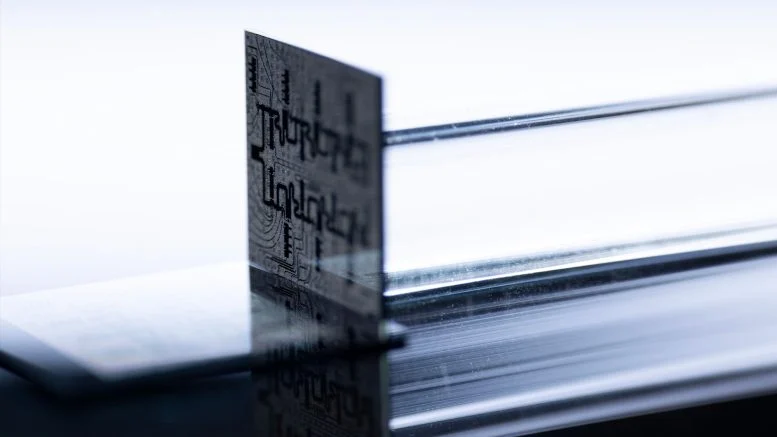

Reporting in the February 26 issue of the journal Nature, a team of scientists from AWS and Caltech demonstrate a new quantum chip architecture for suppressing errors using a type of qubit known as a cat qubit. Cat qubits were first proposed in 2001, and, since then, researchers have developed and refined them. Now, the AWS team has put together the first scalable cat qubit chip that can be used to efficiently reduce quantum errors. Called Ocelot, the new quantum computing chip is named after the spotted wild cat, while also giving a nod to internal “oscillator” technology that underlies the cat qubits.

“For quantum computers to be successful, we need error rates to be about a billion times better than they are today,” says Oskar Painter (PhD ’01), John G Braun Professor of Applied Physics and Physics at Caltech and head of quantum hardware at AWS. “Error rates have been going down about a factor of two every two years. At this rate, it would take us 70 years to get to where we need to be. Instead, we are developing a new chip architecture that may be able to get us there faster. That said, this is an early building block. We still have a lot of work to do.”

The Fragility of Qubits

Qubits are based on 1s and 0s like those in classical computers but the 1s and 0s are in a state of superposition. That means they can take on any combination of 1 and 0 simultaneously. It also means that they are fragile and can very easily fall out of superposition. “What makes qubits powerful also makes them sensitive to quantum errors,” Painter says.

Classical digital computer systems have a straightforward way of handling errors. Basically, the designers of these systems use additional redundant bits to protect data from errors. For example, a single bit of information is replicated across three bits, so that any one bit has two backup partners. If one of those bits has an error (flips from 1 to 0 or 0 to 1), and the other two haven’t flipped, a simple code — in this case, what is called a three-bit repetition code — can be used to detect the error and restore the odd bit out.

The Overhead Problem in Quantum Computing

Due to the complexity of superposition found in qubits, they can have two types of errors: bit flips, as in the classical digital systems, and phase flips, in which the qubit states of 1 and 0 become out of phase (or out of sync) with each other. Researchers have developed many strategies to handle both error types in quantum systems, but the methods require qubits to have a significant number of backup partners. In fact, current qubit technologies may require thousands of additional qubits to provide the desired level of protection from errors. This would be like a newspaper outlet employing a huge building of fact checkers to verify the accuracy of its articles instead of just a small team. The overhead for quantum computers is excessive and unwieldy.

“We are on a long-term quest to build a useful quantum computer to do things even the best supercomputers cannot do, but scaling them up is a huge challenge,” says study co-author Fernando Brandão, Bren Professor of Theoretical Physics at Caltech and director of applied science at AWS. “So, we are trying new approaches to error correction that will reduce the overhead.”

How Cat Qubits Reduce Errors

The team’s new scheme relies on a type of qubit formed from superconducting circuits made of microwave oscillators, in which the 1 and 0 states representing the qubit are defined as two different large-scale amplitudes of oscillation. This makes the qubit states very stable and impervious to bit-flip errors. “You can think of the two oscillating states as being that of a child on a swing, who is swinging at high amplitudes, but is either swinging to the left or to the right. A wind might come up and jostle the swing, but the amplitude of oscillation is so large that it can’t rapidly switch from one direction of swinging to the other,” Painter explains.

In fact, the name “cat” qubits refers to the ability of these qubits to take on two very large, or macroscopic states, at the same time — just like the famous cat in Erwin Schrödinger’s thought experiment, which can be both dead and alive simultaneously.

A More Scalable Quantum Future

With the cat qubits having dramatically reduced bit-flip errors, the only errors left to correct are the phase flip errors. And correcting just one type of error means that the researchers can use a repetition code like those used to fix bit-flip errors in classical systems.

“A classical code like the repetition code in Ocelot means that the new chips will not require as many qubits to correct errors,” Brandão says. “We have demonstrated a more scalable architecture that can reduce the number of additional qubits needed for error correction by up to 90 percent.”

The Ocelot Chip’s Breakthrough

The Ocelot chip achieves this by combining five cat qubits, along with special buffer circuits to stabilize their oscillation, and four ancillary qubits to detect phase errors. The results presented in the Nature article show that the team’s simple repetition code is effective at catching the phase flip errors and improves as the code increases from three cat qubits to five cat qubits. What is more, the phase error-detection process was implemented in a way that maintained a high level of bit-flip error suppression in the cat qubits.

This proof-of-concept demonstration still has a way to go, but Painter says he is excited by the performance that Ocelot has demonstrated so quickly and that the team is doing more research to scale up the technology. “It’s a very hard problem to tackle, and we will need to continue to invest in basic research, while staying connected to, and learning from, important work being done in academia,” he says.

Reference: “Hardware-efficient quantum error correction via concatenated bosonic qubits” by Harald Putterman, Kyungjoo Noh, Connor T. Hann, Gregory S. MacCabe, Shahriar Aghaeimeibodi, Rishi N. Patel, Menyoung Lee, William M. Jones, Hesam Moradinejad, Roberto Rodriguez, Neha Mahuli, Jefferson Rose, John Clai Owens, Harry Levine, Emma Rosenfeld, Philip Reinhold, Lorenzo Moncelsi, Joshua Ari Alcid, Nasser Alidoust, Patricio Arrangoiz-Arriola, James Barnett, Przemyslaw Bienias, Hugh A. Carson, Cliff Chen, Li Chen, Harutiun Chinkezian, Eric M. Chisholm, Ming-Han Chou, Aashish Clerk, Andrew Clifford, R. Cosmic, Ana Valdes Curiel, Erik Davis, Laura DeLorenzo, J. Mitchell D’Ewart, Art Diky, Nathan D’Souza, Philipp T. Dumitrescu, Shmuel Eisenmann, Essam Elkhouly, Glen Evenbly, Michael T. Fang, Yawen Fang, Matthew J. Fling, Warren Fon, Gabriel Garcia, Alexey V. Gorshkov, Julia A. Grant, Mason J. Gray, Sebastian Grimberg, Arne L. Grimsmo, Arbel Haim, Justin Hand, Yuan He, Mike Hernandez, David Hover, Jimmy S. C. Hung, Matthew Hunt, Joe Iverson, Ignace Jarrige, Jean-Christophe Jaskula, Liang Jiang, Mahmoud Kalaee, Rassul Karabalin, Peter J. Karalekas, Andrew J. Keller, Amirhossein Khalajhedayati, Aleksander Kubica, Hanho Lee, Catherine Leroux, Simon Lieu, Victor Ly, Keven Villegas Madrigal, Guillaume Marcaud, Gavin McCabe, Cody Miles, Ashley Milsted, Joaquin Minguzzi, Anurag Mishra, Biswaroop Mukherjee, Mahdi Naghiloo, Eric Oblepias, Gerson Ortuno, Jason Pagdilao, Nicola Pancotti, Ashley Panduro, JP Paquette, Minje Park, Gregory A. Peairs, David Perello, Eric C. Peterson, Sophia Ponte, John Preskill, Johnson Qiao, Gil Refael, Rachel Resnick, Alex Retzker, Omar A. Reyna, Marc Runyan, Colm A. Ryan, Abdulrahman Sahmoud, Ernesto Sanchez, Rohan Sanil, Krishanu Sankar, Yuki Sato, Thomas Scaffidi, Salome Siavoshi, Prasahnt Sivarajah, Trenton Skogland, Chun-Ju Su, Loren J. Swenson, Stephanie M. Teo, Astrid Tomada, Giacomo Torlai, E. Alex Wollack, Yufeng Ye, Jessica A. Zerrudo, Kailing Zhang, Fernando G. S. L. Brandão, Matthew H. Matheny and Oskar Painter, 26 February 2025, Nature.

DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-08642-7

Leave a Reply