By Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research (MPS) February 1, 2025

Collected at: https://scitechdaily.com/ceres-hidden-secrets-unveiling-a-cryovolcanic-giant-in-the-asteroid-belt/

Bright yellow deposits in Consus Crater provide new evidence of Ceres’ cryovolcanic history, reigniting the debate over whether the dwarf planet formed in the asteroid belt or migrated there.

Dwarf planet Ceres may have formed in the asteroid belt rather than migrating there from the outer Solar System. This possibility is supported by bright, ammonium-rich deposits found in Consus Crater, according to a study published in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets by a research team from the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research (MPS) in Göttingen.

The team analyzed data from NASA’s Dawn space probe, which previously detected widespread ammonium deposits on Ceres’ surface. Some scientists have suggested that frozen ammonium, which is only stable in the outer Solar System, played a role in Ceres’ formation, implying that the dwarf planet originated far from its current location. However, the new study presents another explanation: the ammonium-rich material in Consus Crater, like other bright deposits on Ceres, may have been brought to the surface through the planet’s unique cryovolcanic activity.

Ceres: A Mysterious World of Cryovolcanism

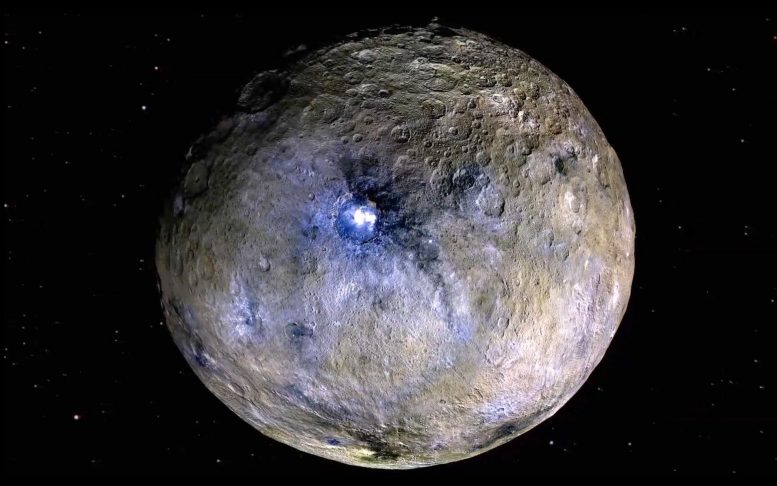

Dwarf planet Ceres stands out in the asteroid belt. At about 960 kilometers in diameter, it is the largest object between Mars and Jupiter. Unlike most of its simpler neighboring asteroids, Ceres has a remarkably complex and diverse geology, hinting at a dynamic history spanning billions of years.

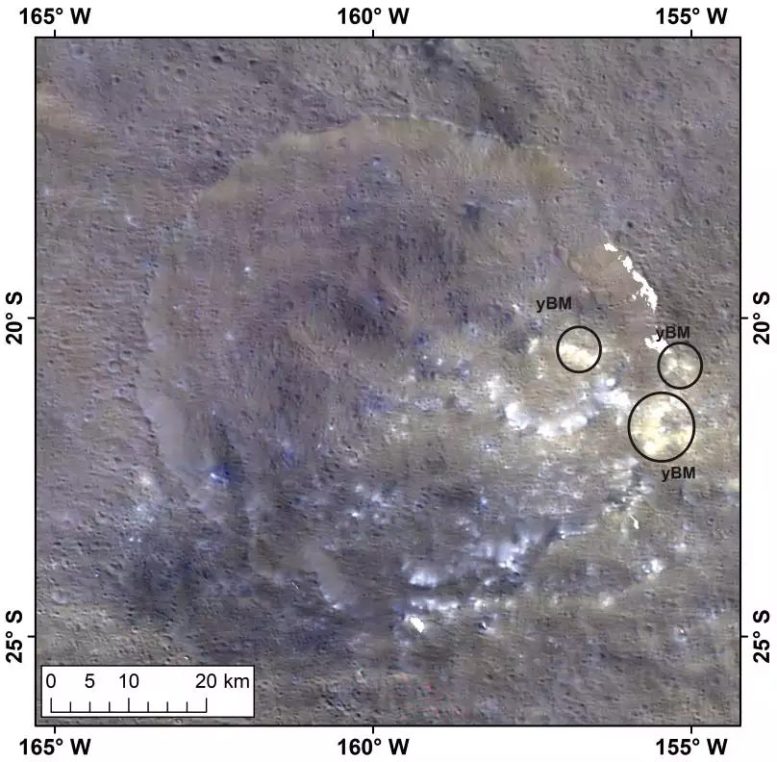

NASA’s Dawn space probe, which explored Ceres from 2015 to 2018, found compelling evidence of ongoing cryovolcanism. Several impact craters contain bright, whitish salt deposits, believed to be remnants of briny liquid that rose from a subsurface layer between the mantle and crust over billions of years. Recent analysis of Consus Crater has revealed similar bright deposits — some with a more yellowish tint — offering new insights into the planet’s geologic evolution.

A Crater Within a Crater

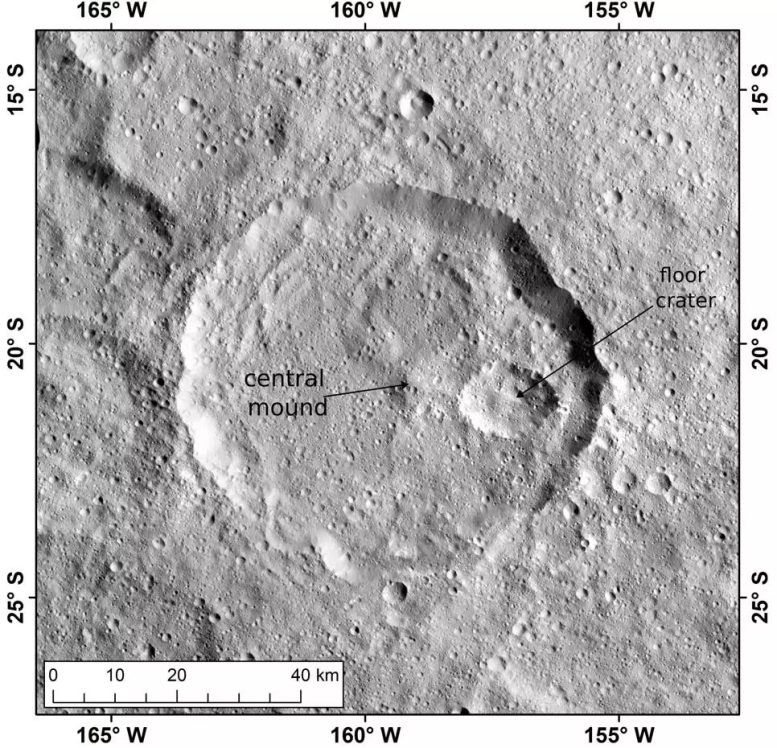

Conus Crater is located on Ceres’ southern hemisphere. With a diameter of around 64 kilometers, it is not one of the dwarf planet’s particularly large impact craters. Images taken by Dawn’s scientific camera system, which was developed and built under the lead of the MPS, show a circumferential crater wall that rises about 4.5 kilometers above the crater floor and has partially eroded inwards. It encloses a smaller crater covering an area of about 15 kilometers by eleven kilometers that dominates the eastern half of Consus’ crater floor. The yellowish, bright material is found in isolated speckles exclusively on the edge of the smaller crater and in an area slightly to the east of it.

Ammonium: A Clue to Ceres’ Origins

As the new analysis of data from the camera system and the VIR spectrometer suggests, the yellowish bright material in Consus Crater is rich in ammonium. In traces, the compound, which differs from ammonia by an additional hydrogen ion, is almost omnipresent on the surface of Ceres in the form of ammonium-rich minerals. In the past, scientists believed that these minerals could only have formed through contact with ammonium ice in the cold at the outer edge of the Solar System, where frozen ammonium is stable over long periods of time. In closer proximity to the Sun, it evaporates quickly. Ceres must therefore have formed at the edge of the Solar System and only later “relocated” to the asteroid belt, they inferred. The current study now shows for the first time a connection between ammonium and the salty brine from Ceres’ interior. The team argues that therefore the dwarf planet’s origin does not necessarily have to be in the outer Solar System. Ceres could also be truly native to the asteroid belt.

Ammonium from the Depths

The researchers assume that the components of ammonium were already contained in Ceres’ original building blocks. As ammonium does not combine with the typical minerals in Ceres’ mantle, it gradually accumulated in a thick layer of brine that extended globally between the dwarf planet’s mantle and crust. Cryovolcanic activity caused the ammonium-rich brine to rise repeatedly over the course of billions of years, and the ammonium it contained gradually seeped into the large-scale phyllosilicates of Ceres’ crust. Phyllosilicates, which are characterized by a layer-like crystal structure, are also widespread on Earth, for example in clayey soils. “The minerals in Ceres’ crust possibly absorbed the ammonium over many billions of years like a kind of sponge,” explains MPS scientist Dr. Andreas Nathues, first author of the current study and former Lead Investigator of Dawn’s camera team.

There is much to suggest that the concentration of ammonium is greater in deeper layers of the crust than near the surface. The few places on the surface of Ceres where conspicuous patches of the yellowish-bright material can be found outside Consus Crater are also located within deep craters. As the current study shows in detail, the impact that created the small eastern crater only 280 million years ago is likely to have exposed material from the deep, particularly ammonium-rich layers in Consus Crater. The yellowish-bright speckles to the east of the smaller crater are material that was ejected as a result of the impact.

A Window into Ceres’ Deep Past

“At 450 million years, Consus Crater is not particularly old by geological standards, but it is one of the oldest surviving structures on Ceres. Due to its deep excavation, it gives us access to processes that took place in the interior of Ceres over many billions of years — and is thus a kind of window into the dwarf planet’s past,” says MPS researcher Dr. Ranjan Sarkar, a co-author of the study.

Reference: “Consus Crater on Ceres: Ammonium-Enriched Brines in Exchange With Phyllosilicates?” by A. Nathues, M. Hoffmann, R. Sarkar, P. Singh, J. Hernandez, J. H. Pasckert, N. Schmedemann, G. Thangjam, E. Cloutis, K. Mengel and M. Coutelier, 5 September 2024, Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets.

DOI: 10.1029/2023JE008150

Leave a Reply