By Brookhaven National Laboratory January 28, 2025

Collected at: https://scitechdaily.com/recreating-the-big-bang-tiny-collisions-reveal-droplets-of-the-universes-first-matter/

Scientists at the PHENIX experiment at RHIC have uncovered compelling evidence that even collisions involving small nuclei with large ones can produce tiny droplets of quark-gluon plasma (QGP), a state of matter believed to have existed moments after the Big Bang.

A recent analysis of data from the PHENIX experiment at the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider (RHIC) has uncovered new evidence suggesting that even collisions between very small and large nuclei can produce tiny droplets of quark-gluon plasma (QGP). Scientists believe that this unique state of matter, made up of free quarks and gluons—the fundamental components of protons and neutrons—existed just moments after the Big Bang. At RHIC, high-energy collisions of gold ions, which are gold atom nuclei stripped of their electrons, regularly create QGP by “melting” these nuclear building blocks. This allows researchers to investigate the plasma’s properties.

Initially, physicists assumed that collisions involving smaller ions wouldn’t generate enough energy to create QGP, as the smaller ion was thought to lack the necessary force to break apart the protons and neutrons in the larger ion. However, data from PHENIX has consistently suggested otherwise. It indicates that even small collision systems can produce particle flow patterns similar to those observed in larger QGP formations. The latest findings, published in Physical Review Letters, strengthen the case for the presence of these tiny droplets of QGP. The study provides the first direct evidence that energetic particles formed in RHIC’s small-scale collisions can lose energy and slow down significantly as they travel outward, a key indicator of QGP formation.

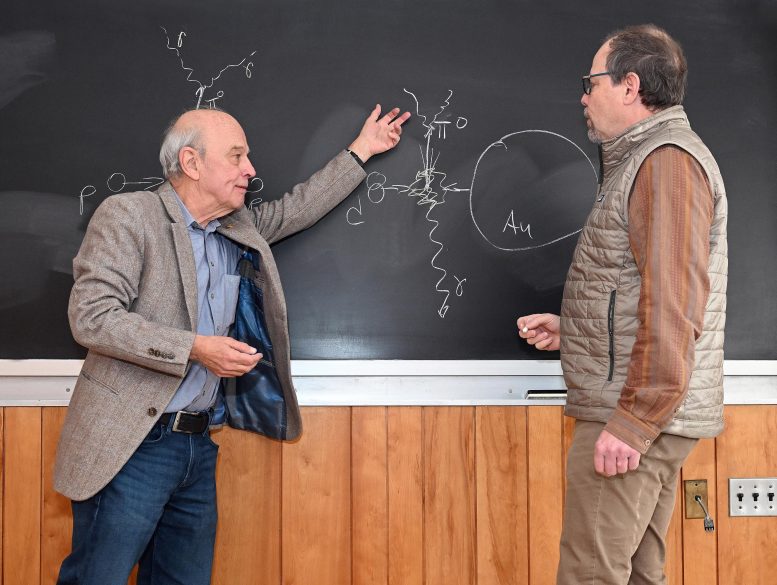

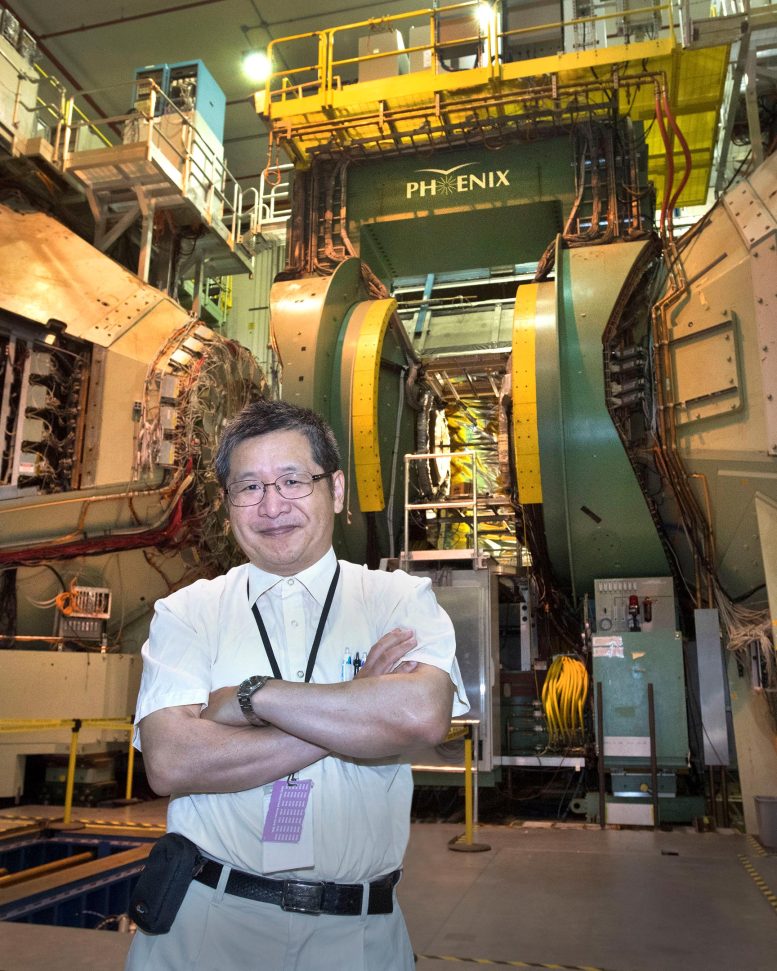

“We found, for the first time in a small collision system, the suppression of energetic particles, which is one of two main pieces of evidence for the QGP,” said PHENIX Collaboration Spokesperson Yasuyuki Akiba, a physicist at Japan’s RIKEN Nishina Center for Accelerator-Based Science and Experiment Group Leader at the RIKEN-BNL Research Center (RBRC) at Brookhaven Lab.

Jet Quenching as a Key Indicator

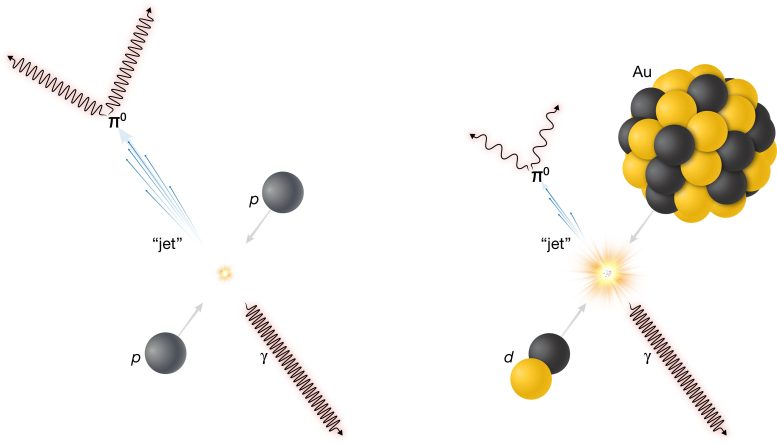

Looking for the suppression of high-energy jets of particles, or jet “quenching,” has been a key goal from the earliest days at RHIC, a DOE Office of Science user facility for nuclear physics research that began operating at Brookhaven Lab in 2000. Jets are created when a quark or gluon within a proton or neutron in one of RHIC’s ion beams collides intensely with a quark or gluon in the nuclear particles that make up the beam traveling in the opposite direction. These strong interactions can kick single quarks or gluons free from the colliding nuclear building blocks with tremendous amounts of energy, which quickly transforms the energetic particles into cascades, or jets, of other particles.

If the collision doesn’t melt the nuclear matter into a soup of free quarks and gluons — the QGP — then these energetic jets of particles, or their decay products, sail out freely to be counted by RHIC’s detectors. But if the collisions do form a QGP, the kicked-free quark or gluon, despite its energy, gets caught up in interactions with the quarks and gluons that make up the plasma.

“Those interactions lead to energy loss,” explained Gabor David, a PHENIX physicist from Stony Brook University (SBU) who was one of the leaders of the new analysis.

“You can think about it like the difference between running through air and running through water,” he said. The QGP is like the water; it slows the particles down. As a result, jets reach the detector with only a fraction of their original energy.

Gold-Gold Collisions Set the Baseline

To look for this suppression, the physicists first must estimate the number of energetic particles that would be expected from the gold-gold smashups by mathematically scaling up from simple proton-proton collisions to the number of protons and neutrons involved in collisions of heavier ions such as gold. The calculated values indirectly indicate whether the collision happens dead-center between the two gold ions or if it’s a glancing collision where the ions sideswipe one another at the edges. Central collisions are expected to create more jets than peripheral ones. But they’re also more likely to generate bigger QGP and therefore higher jet suppression.

This method has worked beautifully for the gold-gold smashups.

“We expected we should see 1,000 times the number of energetic particles, or jets, in the most central gold-gold collisions compared to proton-proton collisions,” Akiba said. “But we saw only about 200 times the proton-proton level, one-fifth the expected number. That’s a factor of five suppression.”

This jet suppression is a clear sign that the gold-gold collisions are generating the QGP. It’s also consistent with another key signature of the QGP formation in these collisions — namely, characteristic patterns of particle flow caused by hydrodynamic properties of the “perfect liquid” plasma.

A Surprising Discrepancy in Small Collisions

When PHENIX scientists observed similar hydrodynamic flow patterns in small collision systems, hinting that there might be tiny drops of the QGP, they set out to search for jet suppression in those events as well. The results were a surprise: While the most central collisions of particles such as deuterons — one proton and one neutron — with gold ions exhibited signs of jet suppression, more peripheral collisions seemed to show an increase in energetic jets.

“There was no explanation for why this should happen — absolutely none,” David said.

Turning to Direct Photons for Answers

As it turns out, the surprising increase was an artifact of the indirect way the physicists had determined the centrality of the collisions. They discovered this by trying an alternate and more direct approach, as described in the new paper. Instead of using calculations based on a geometric model to estimate the number of nuclear particles — protons and neutrons — participating in the collisions, they used a direct measurement of those interactions by counting so-called “direct” photons.

This is possible because just as a RHIC collision can kick an energetic quark or gluon free, that interaction can also produce a high energy photon, or particle of light. These direct photons are produced in the collision right along with and in amounts proportional to the kicked-free quarks and gluons.

So, by counting the direct photons that strike their detector, the PHENIX scientists could directly measure the centrality of the collisions and know exactly how many energetic quarks or gluons were kicked free — that is, how many jets to expect.

“The more central the collision is, the more interactions there can be between the quarks and gluons of a small colliding deuteron with the quarks and gluons in the protons and neutrons of a gold ion,” explained Axel Drees of SBU, another leader of the analysis. “So, central smashups produce more direct photons and should produce more energetic jet particles than glancing collisions do.”

But unlike the quarks and gluons, the photons don’t interact with the QGP.

“If photons are created, they escape the QGP completely without any energy loss,” Drees said.

So, if there’s no QGP, the photons and energetic particles should be detected in proportionate amounts. But if in central collisions the number of energetic jet particles detected is significantly lower than the number of direct photons of the same energy, that could be a sign that a QGP is present, quenching the jets.

Niveditha Ramasubramanian, who was a graduate student advised by David at the time, undertook the challenging task of teasing out the direct photon signals from PHENIX’s deuteron-gold collision data. When her analysis was complete, the earlier, unexplained increase in jets emerging from peripheral collisions completely disappeared. But there was still a strong signal of suppression in the most central collisions.

Unambiguous Evidence of QGP Suppression

“The initial motivation to do this complex analysis was only to better understand the strange increase in energetic jets in peripheral collisions, which we did,” said Ramasubramanian, a co-author on the paper who earned her Ph.D. — and a Thesis Award at the 2022 RHIC & AGS Users Meeting — for her contributions to this result. Now a staff scientist at the French National Centre for Scientific Research, she added, “The suppression that we observed in the most central collisions was entirely unexpected.”

“When we use the direct photons as a precise, accurate measure of the collision centrality, we can see the suppression [in central collisions] unambiguously,” Akiba said.

David noted that, “The new method relies solely on observable quantities, avoiding the use of theoretical models.”

Future Steps and Further Investigations

The next step will be to apply the same method to other small collision systems.

“Ongoing analyses of PHENIX’s proton-gold and helium-3-gold data with the same technique will help to further clarify the origins of this suppression to confirm our current understanding or rule it out by competing explanations,” Drees said.

Reference: “Disentangling Centrality Bias and Final-State Effects in the Production of High-𝑝𝑇 Neutral Pions Using Direct Photon in 𝑑+Au Collisions at √𝑠𝑁𝑁=200 GeV” by N. J. Abdulameer, U. Acharya, C. Aidala, Y. Akiba, M. Alfred, K. Aoki, N. Apadula, C. Ayuso, V. Babintsev, V. Babintsev, K. N. Barish, S. Bathe, A. Bazilevsky, R. Belmont, A. Berdnikov, Y. Berdnikov, L. Bichon, B. Blankenship, D. S. Blau, M. Boer, J. S. Bok, V. Borisov, M. L. Brooks, J. Bryslawskyj, V. Bumazhnov, C. Butler, S. Campbell, V. Canoa Roman, M. Chiu, M. Connors, R. Corliss, Y. Corrales Morales, M. Csanád, T. Csörgő, L. D. Liu, T. W. Danley, M. S. Daugherity, G. David, C. T. Dean, K. DeBlasio, K. Dehmelt, A. Denisov, A. Deshpande, E. J. Desmond, V. Doomra, J. H. Do, A. Drees, K. A. Drees, M. Dumancic, J. M. Durham, A. Durum, T. Elder, A. Enokizono, R. Esha, B. Fadem, W. Fan, N. Feege, M. Finger, Jr., M. Finger, D. Firak, D. Fitzgerald, S. L. Fokin, J. E. Frantz, A. Franz, A. D. Frawley, Y. Fukuda, C. Gal, P. Garg, H. Ge, M. Giles, Y. Goto, N. Grau, S. V. Greene, T. Gunji, T. Hachiya, J. S. Haggerty, K. I. Hahn, S. Y. Han, M. Harvey, S. Hasegawa, T. O. S. Haseler, T. K. Hemmick, X. He, K. Hill, A. Hodges, K. Homma, B. Hong, T. Hoshino, N. Hotvedt, J. Huang, J. Imrek, M. Inaba, D. Isenhower, Y. Ito, D. Ivanishchev, B. V. Jacak, Z. Ji, B. M. Johnson, V. Jorjadze, D. Jouan, D. S. Jumper, J. H. Kang, D. Kapukchyan, S. Karthas, A. V. Kazantsev, V. Khachatryan, A. Khanzadeev, A. Khatiwada, C. Kim, D. J. Kim, E.-J. Kim, M. Kim, M. H. Kim, T. Kim, D. Kincses, A. Kingan, E. Kistenev, T. Koblesky, D. Kotov, L. Kovacs, S. Kudo, B. Kurgyis, K. Kurita, J. G. Lajoie, E. O. Lallow, D. Larionova, A. Lebedev, S. H. Lee, M. J. Leitch, Y. H. Leung, N. A. Lewis, S. H. Lim, M. X. Liu, X. Li, V.-R. Loggins, D. A. Loomis, D. Lynch, S. Lökös, T. Majoros, M. Makek, M. Malaev, V. I. Manko, E. Mannel, H. Masuda, M. McCumber, D. McGlinchey, A. C. Mignerey, D. E. Mihalik, A. Milov, D. K. Mishra, J. T. Mitchell, M. Mitrankova, Iu. Mitrankov, G. Mitsuka, M. M. Mondal, T. Moon, D. P. Morrison, S. I. Morrow, A. Muhammad, B. Mulilo, T. Murakami, J. Murata, K. Nagai, K. Nagashima, T. Nagashima, J. L. Nagle, M. I. Nagy, I. Nakagawa, H. Nakagomi, K. Nakano, C. Nattrass, S. Nelson, R. Nouicer, N. Novitzky, R. Novotny, T. Novák, G. Nukazuka, A. S. Nyanin, E. O’Brien, C. A. Ogilvie, J. Oh, J. D. Orjuela Koop, M. Orosz, J. D. Osborn, A. Oskarsson, K. Ozawa, V. Pantuev, V. Papavassiliou, J. S. Park, S. Park, M. Patel, S. F. Pate, W. Peng, D. V. Perepelitsa, G. D. N. Perera, C. E. PerezLara, R. Petti, M. Phipps, C. Pinkenburg, M. Potekhin, A. Pun, M. L. Purschke, P. V. Radzevich, N. Ramasubramanian, K. F. Read, V. Riabov, Y. Riabov, D. Richford, T. Rinn, M. Rosati, Z. Rowan, J. Runchey, T. Sakaguchi, H. Sako, V. Samsonov, M. Sarsour, K. Sato, S. Sato, B. Schaefer, B. K. Schmoll, R. Seidl, A. Sen, R. Seto, A. Sexton, D. Sharma, I. Shein, M. Shibata, T.-A. Shibata, K. Shigaki, M. Shimomura, Z. Shi, C. L. Silva, D. Silvermyr, M. Slunečka, K. L. Smith, S. P. Sorensen, I. V. Sourikova, P. W. Stankus, S. P. Stoll, T. Sugitate, A. Sukhanov, Z. Sun, S. Syed, R. Takahama, A. Takeda, K. Tanida, M. J. Tannenbaum, S. Tarafdar, A. Taranenko, G. Tarnai, R. Tieulent, A. Timilsina, T. Todoroki, M. Tomášek, C. L. Towell, R. S. Towell, I. Tserruya, Y. Ueda, B. Ujvari, H. W. van Hecke, S. Vazquez-Carson, J. Velkovska, M. Virius, V. Vrba, X. R. Wang, Z. Wang, Y. Watanabe, C. P. Wong, C. Xu, Q. Xu, Y. L. Yamaguchi, A. Yanovich, P. Yin, I. Yoon, J. H. Yoo, I. E. Yushmanov, H. Yu, W. A. Zajc and L. Zou, 15 January 2025, Physical Review Letters.

DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.134.022302

This research was funded by the DOE Office of Science (NP), the National Science Foundation, and a range of U.S. and international universities and organizations listed in the scientific paper. The PHENIX experiment collected data at RHIC from 2000 until 2016 and, as this paper indicates, analysis of its data is ongoing.

Leave a Reply