By Vienna University of Technology January 20, 2026

Collected at: https://scitechdaily.com/this-quantum-material-breaks-the-rules-and-reveals-new-physics/

Electrons are usually described as particles, but in a rare quantum material, that picture completely breaks down.

Quantum physics shows that particles do not behave like solid objects with fixed positions. Instead, they also act like waves, which means their exact location in space cannot be pinned down. Even so, in many practical situations, scientists can still rely on a familiar, classical description. They often picture particles as tiny objects moving through space at a certain speed.

This simplified view is especially useful when explaining how electricity moves through metals. Physicists typically describe electric current as electrons rushing through a material, where they are pushed, slowed, or redirected by electromagnetic forces.

When the Particle Picture Breaks Down

Many modern theories also build on this particle-based description. One prominent example is the idea of topological states of matter, a breakthrough that earned the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2016. These theories assume that electrons behave like particles with clear energies and velocities.

However, researchers have identified materials in which this picture no longer applies (see publication below). In these cases, electrons cannot be described as small objects with a precise position or a single, well-defined speed.

Now, a team at TU Wien has shown that even when electrons lose this particle-like behavior, the material can still exhibit topological properties. Until now, such properties had always been explained using particle-based models. The new results show that topology applies more broadly than expected, bringing together ideas that once seemed incompatible.

When the Particle Picture No Longer Makes Sense

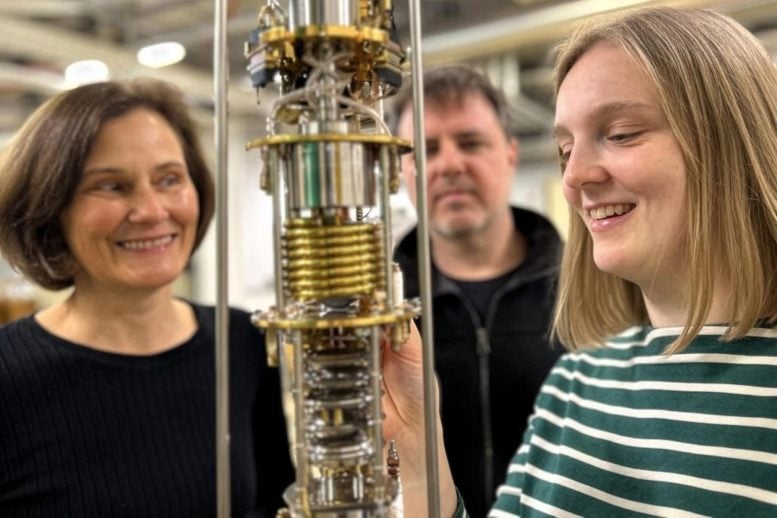

“The classical picture of electrons as small particles that suffer collisions as they flow through a material as an electric current is surprisingly robust,” says Prof. Silke Bühler-Paschen from the Institute of Solid State Physics at TU Wien. “With certain refinements, it works even in complex materials where electrons interact strongly with one another.”

There are extreme situations, however, where this description fails entirely. In these cases, charge carriers lose their particle-like character. This behavior appears in a compound made of cerium, ruthenium and tin (CeRu₄Sn₆), which researchers at TU Wien studied at extremely low temperatures.

“Near absolute zero, it exhibits a specific type of quantum-critical behavior,” says Diana Kirschbaum, first author of the current publication. “The material fluctuates between two different states, as if it cannot decide which one it wants to adopt. In this fluctuating regime, the quasiparticle picture is thought to lose its meaning.”

What Topology Has to Do With Donuts

At the same time, theoretical studies suggested that this same material should host topological states. “The term topology comes from mathematics, where it is used to distinguish certain geometric structures,” explains Silke Bühler-Paschen.

“For example, an apple is topologically equivalent to a bread roll, because the roll can be continuously deformed into the shape of an apple. A roll is topologically different from a donut, however, because the donut has a hole that cannot be created by continuous deformation.”

Physicists use similar ideas to describe states of matter. Quantities such as particle energy, velocity, and even the direction of spin relative to motion can follow specific geometric patterns. These patterns are especially important because they are highly stable. Minor disruptions, such as defects in a material, do not destroy them, just as small shape changes cannot turn a donut into an apple.

Because of this robustness, topological effects are considered promising for applications like quantum information storage, new types of sensors, and guiding electric currents without magnetic fields.

A Theoretical Puzzle

Although topology may sound abstract, most existing theories still rely indirectly on the particle picture. “These theories assume that one is describing something with well-defined velocities and energies,” explains Diana Kirschbaum.

“But such well-defined velocities and energies do not seem to exist in our material, because it exhibits a form of quantum-critical behavior that is considered to be incompatible with a particle picture. Nevertheless, simple theoretical approaches that ignore these non-particle-like properties had previously predicted that the material should show topological characteristics.”

This left researchers with a clear contradiction between theory and expected physical behavior.

Curiosity Leads to Experimental Proof

Because of this conflict, Bühler-Paschen’s team initially hesitated to follow up on the theoretical prediction. Eventually, curiosity took over, and Diana Kirschbaum began searching for experimental evidence of topological behavior.

At temperatures less than one degree above absolute zero, she observed a clear signal: a spontaneous (anomalous) Hall effect. Normally, the Hall effect occurs when charge carriers are deflected by a magnetic field. In this case, however, the deflection appeared even though no external magnetic field was applied.

What made the result especially striking was that the charge carriers behaved as if they were particles, despite strong evidence that the particle picture should not apply. “This was the key insight that allowed us to demonstrate beyond doubt that the prevailing view must be revised,” says Silke Bühler-Paschen.

“And there is more,” adds Diana Kirschbaum. “The topological effect is strongest precisely where the material exhibits the largest fluctuations. When these fluctuations are suppressed by pressure or magnetic fields, the topological properties disappear.”

Rethinking Topological States of Matter

“This was a huge surprise,” says Silke Bühler-Paschen. “It shows that topological states should be defined in generalized terms.”

The researchers describe the newly identified phase as an emergent topological semimetal. They collaborated with Rice University in Texas, where Lei Chen (co-first author of the publication), working in the group of Prof. Qimiao Si, developed a theoretical model that successfully connects quantum criticality with topology.

“In fact, it turns out that a particle picture is not required to generate topological properties,” says Bühler-Paschen. “The concept can indeed be generalized—the topological distinctions then emerge in a more abstract, mathematical way. And more than that: our experiments suggest that topological properties can even arise because particle-like states are absent.”

A New Strategy for Discovering Quantum Materials

The findings also point to practical opportunities. They suggest a new way to search for topological materials by focusing on systems that show quantum-critical behavior.

“We now know that it is worthwhile—perhaps even particularly worthwhile—to search for topological properties in quantum-critical materials,” Bühler-Paschen says. “Because quantum-critical behavior occurs in many classes of materials and can be reliably identified, this connection may allow many new ’emergent’ topological materials to be discovered.”

Reference: “Emergent topological semimetal from quantum criticality” by D. M. Kirschbaum, L. Chen, D. A. Zocco, H. Hu, F. Mazza, M. Karlich, M. Lužnik, D. H. Nguyen, J. Larrea Jiménez, A. M. Strydom, D. Adroja, X. Yan, A. Prokofiev, Q. Si and S. Paschen, 14 January 2026, Nature Physics.

DOI: 10.1038/s41567-025-03135-w

Leave a Reply