December 19, 2025 by Sam Jarman, Phys.org

Collected at: https://phys.org/news/2025-12-machine-microscopy-year-mystery-premelting.html

Through a novel combination of machine learning and atomic force microscopy, researchers in China have unveiled the molecular surface structure of “premelted” ice, resolving a long-standing mystery surrounding the liquid-like layer which forms on icy surfaces.

Detailed in a study in Physical Review X, the approach could also be applied more widely to reveal surface features that are too challenging for existing microscopy techniques to resolve.

Background on premelting and its significance

While ice has a well-defined melting point, a thin, liquid-like layer can form on its surface even at temperatures far below freezing. Known as ‘”premelting,” this effect was first noted over 170 years ago by Michael Faraday, through his careful observations of melting ice.

Since then, the effect has been extensively explored for its influence on properties including friction, chemical reactivity, and atmospheric chemistry, and has been exploited in areas ranging from cryopreservation to ice skating.

However, “despite this long history, the microscopic structure of the premelted layer has remained poorly understood,” says Jiani Hong at Peking University, Beijing, who was one of the study’s co-authors. “This is largely because experimental access to disordered interfacial structures and their dynamics at the atomic scale is extremely challenging.”

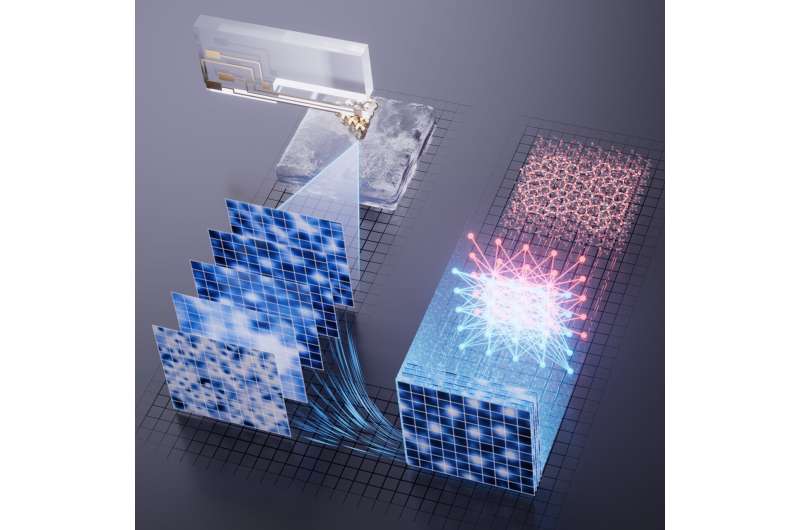

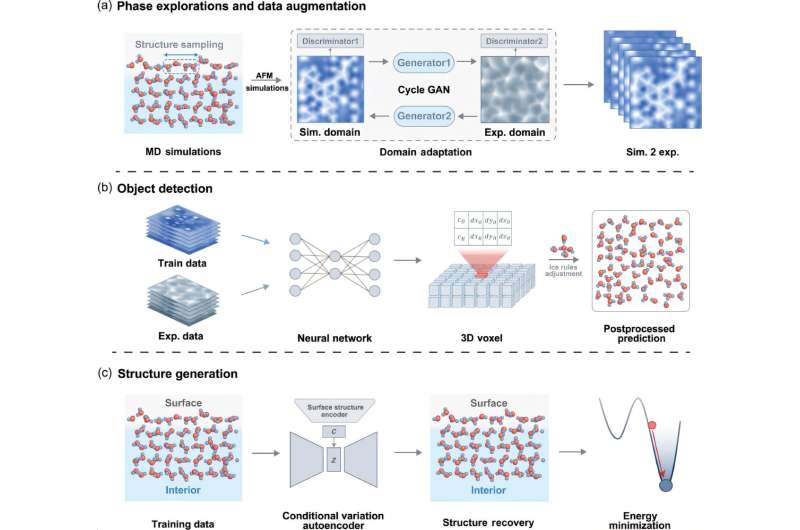

Schematic illustration of the overall framework of the training and prediction processes. Credit: Physical Review X (2025). DOI: 10.1103/9fzf-y9n9

Advances in imaging and machine learning

In their previous work, Hong’s team, under the joint leadership of Prof. Limei Xu and Prof. Ying Jiang at Peking University, made significant strides toward a technique for studying the surface structure of ice at the onset of premelting. Their approach involved atomic force microscopy (AFM): a technique which gathers information by moving a tiny mechanical probe across a sample surface.

By scanning the probe at a controlled distance above the surface, the instrument translates tiny changes in the force experienced by the probe’s tip into an electrical signal—allowing researchers to map out topological surface landscapes down to atomic scales.

But when observing the subtle features that emerge during premelting, even this level of resolution falls short. Since AFM is intrinsically surface-sensitive, it can’t fully recover the 3D atomic structures of disordered surfaces from surface contrast alone.

In their latest study, Xu’s team addressed this challenge by combining the technique with a machine learning framework, trained specifically to detect these features. To train the algorithm, they used molecular dynamics simulations augmented with realistic experimental noise.

With this approach, they could finally reconstruct the molecular-scale surface features which couldn’t be recovered from AFM, or predicted from simulations alone.

“These experimentally resolved structures can then serve as realistic starting points for simulations, allowing us to explore interfacial dynamics and phase transitions that were previously inaccessible,” Hong explains.

Discovery of the amorphous surface layer

Between temperatures of –152 °C and –93 °C, the new simulations revealed for the first time that an ‘amorphous’ layer forms on the surface of ice—where it is still frozen solid, but its water molecules lack the orderly lattice structure found in ordinary crystalline ice.

“This layer exhibits strong topological disorder while retaining solid-like dynamics, and it gradually evolves into a quasi-liquid layer as the temperature increases,” Hong explains.

The researchers are confident that their discovery redefines the microscopic picture of premelted ice, and provides an entirely new perspective on how its crystal surface grows and evolves at temperatures well below freezing.

Yet beyond solving this long-standing puzzle, they also hope that their novel technique could be applied more broadly to capturing elusive surface features.

“The machine learning AFM framework provides a powerful atomic-scale tool to investigate disordered interfaces, phase transitions, and material defects, with broad potential applications in catalytic interfaces, functional materials, and biological systems,” Hong says.

More information: Binze Tang et al, Unveiling the Amorphous Ice Layer during Premelting Using AFM Integrating Machine Learning, Physical Review X (2025). DOI: 10.1103/9fzf-y9n9

Journal information: Physical Review X

Leave a Reply