By Helmholtz-Zentrum Dresden-Rossendorf December 18, 2025

Collected at: https://scitechdaily.com/physicists-propose-first-ever-experiment-to-manipulate-gravitational-waves/

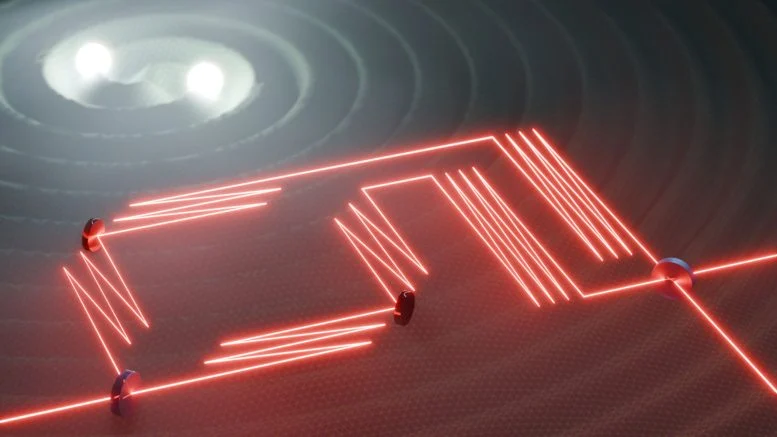

A new concept for energy transfer between gravitational waves and light.

When massive cosmic objects such as black holes merge or neutron stars crash into one another, they can produce gravitational waves. These ripples move through the universe at the speed of light and create extremely small changes in the structure of space-time. Their existence was first predicted by Albert Einstein, and scientists confirmed them experimentally for the first time in 2015.

Building on this discovery, Prof. Ralf Schützhold, a theoretical physicist at the Helmholtz-Zentrum Dresden-Rossendorf (HZDR), is proposing a bold new step.

Schützhold has developed a concept for an experiment that would go beyond detecting gravitational waves and instead allow researchers to influence them. The proposal, published in the journal Physical Review Letters, could also help clarify whether gravity follows quantum rules, a question that remains unresolved in modern physics.

Manipulating Gravitational Waves With Light

“Gravity affects everything, including light,” says Schützhold. And this interaction also occurs when gravitational waves and light waves meet. Schützhold’s idea is to transfer tiny packets of energy from a light wave to a gravitational wave. By doing so, the energy of the light wave is reduced slightly, and the energy of the gravitational wave is increased by the same amount.

The transferred energy corresponds to one or more gravitons, the hypothetical particles that are thought to carry the force of gravity in quantum theories, but which have not yet been directly observed.

“It would make the gravitational wave a tiny bit more intensive,” explains the physicist. The light wave, on the other hand, loses exactly the same amount of energy which leads to a minute change in the light wave’s frequency.

“The process can work the other way around, too,” Schützhold continues. In this case, the gravitational wave dispenses an energy package to the light wave. It should be possible to measure both effects, that is, the stimulated emission and absorption of gravitons, albeit with considerable experimental effort.

An Experiment on an Extreme Scale

Schützhold has calculated the huge dimensions of such an experiment: potentially, laser pulses in the visible or near-infrared spectral range could be reflected back and forth between two mirrors up to a million times. In a set-up about a kilometer long, this would produce an optical path length of around one million kilometers. Such an order of magnitude is sufficient to conduct the desired measurement of the energy exchange caused by the absorption and emission of gravitons when light and a gravitational wave meet.

However, the change in the frequency of the light wave caused by the absorption or release of the energy of one or more gravitons in interaction with the gravitational wave is extremely small. Nevertheless, by using a cleverly constructed interferometer it should be possible to demonstrate these changes in frequency.

In the process, two light waves experience different changes in frequency – depending on whether they absorb or emit gravitons. After this interaction and passing along the optical path length, they overlap again and generate an interference pattern. From this, it is possible to infer the frequency change that has occurred and thus the transfer of gravitons.

Probing the Quantum Nature of Gravity

“It can take several decades from initial idea to experiment,” says Schützhold. But perhaps it might happen sooner in this case, as the LIGO Observatory – acronym for the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory – that is dedicated to detecting gravitational waves, shows strong similarities. LIGO consists of two L-shaped vacuum tubes approximately four kilometers long.

A beam splitter divides a laser beam onto both arms of the detector. As they pass through, incoming gravitational waves minimally distort space-time, which causes changes of a few attometers (10-18 meters) in the originally equal length of the two arms. This tiny change in length alters the interference pattern of the laser light, generating a detectable signal.

In an interferometer tailored to Schützhold’s idea, it could be possible not only to observe gravitational waves but also to manipulate them for the first time by stimulated emission and absorption of gravitons. According to Schützhold, light pulses whose photons are entangled, that is, quantum mechanically coupled, could significantly increase the sensitivity of the interferometer further.

“Then we could even draw inferences about the quantum state of the gravitational field itself,” says Schützhold. While this would not be direct proof of the hypothetical graviton, which is the subject of intense debate among physicists, it would at least be a strong indication of its existence.

After all, if the light waves did not exhibit the predicted interference effects when interacting with gravitational waves, the current theory based on gravitons would be disproved. It is thus hardly surprising that Schützhold’s concept for the manipulation of gravitational waves is meeting with great interest among his colleagues.

Reference: “Stimulated Emission or Absorption of Gravitons by Light” by Ralf Schützhold, 22 October 2025, Physical Review Letters.

DOI: 10.1103/xd97-c6d7

Leave a Reply