By University of California, Los Angeles December 13, 2025

Collected at: https://scitechdaily.com/an-old-jewelers-trick-could-unlock-the-next-generation-of-nuclear-clocks/

A revolutionary achievement could pave the way for smaller, more efficient nuclear clocks.

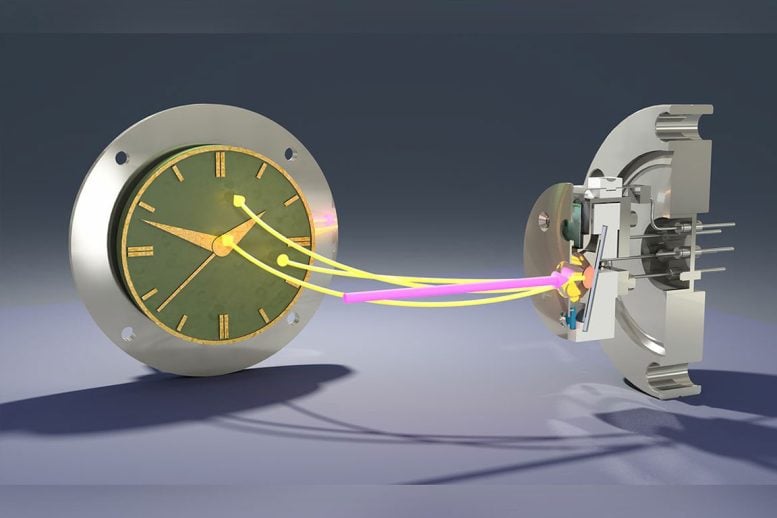

Last year, a research team led by UCLA achieved a milestone scientists had pursued for half a century. They succeeded in making radioactive thorium nuclei interact with light by absorbing and emitting photons, similar to how electrons behave inside atoms. First envisioned by the group in 2008, the breakthrough is expected to transform precision timekeeping and could significantly improve navigation systems, while also opening the door to discoveries that challenge some of the most basic constants in physics.

The advance comes with a major limitation. The required isotope, thorium-229, exists only as a byproduct of weapons-grade uranium, making it extremely rare. Researchers estimate that just 40 grams of this material are currently available worldwide for use in nuclear clock research.

A new study now shows a way around this obstacle. An international collaboration led by UCLA physicist Eric Hudson has developed an approach that uses only a small fraction of the thorium needed in earlier experiments, while delivering the same results previously achieved with specialized crystals. Described in Nature, the technique is both straightforward and low cost, raising the possibility that nuclear clocks could one day be small and affordable enough to fit into everyday devices like phones or wristwatches. Beyond consumer electronics, the clocks could replace existing systems used in power grids, cell phone towers, and GPS satellites, and may even support navigation where GPS is unavailable, such as in deep space or underwater.

A simple process improves what originally took 15 years to figure out

Hudson’s team spent 15 years developing the specialized thorium-doped fluoride crystals that enabled last year’s breakthrough. In those early experiments, thorium-229 atoms were bonded with fluorine in a carefully controlled structure that kept the radioactive material stable while allowing laser light to pass through and excite the nucleus. While effective, the crystals were challenging to produce and required relatively large amounts of the scarce thorium isotope.

“We did all the work of making the crystals because we thought the crystal had to be transparent for the laser light to reach the thorium nuclei. The crystals are really challenging to fabricate. It takes forever and the smallest amount of thorium we can use is 1 milligram, which is a lot when there’s only 40 or so grams available,” said first author and UCLA postdoctoral researcher Ricky Elwell, who received the 2025 Deborah Jin Award for Outstanding Doctoral Thesis Research in Atomic, Molecular, or Optical Physics for last year’s breakthrough.

In the new work, Hudson’s group electroplated a minute amount of thorium onto stainless steel by slightly modifying a method used to electroplate jewelry. Electroplating, which was invented in the early 1800s, sends an electric current through an electrically conductive solution to deposit a thin layer of atoms from one metal onto another. In jewelry, for example, silver or gold is electroplated onto a less precious metal base.

“It took us five years to figure out how to grow the fluoride crystals and now we’ve figured out how to get the same results with one of the oldest industrial techniques and using 1,000 times less thorium. Further, the finished product is essentially a small piece of steel and much tougher than the fragile crystals,” said Hudson.

The key to getting this new system working was the realization that one fundamental assumption was wrong. Stimulating the nucleus enough with a laser, or exciting it, to observe its transition to a higher energy state, was easier than anyone thought

“Everyone had always assumed that in order to excite and then observe the nuclear transition, the thorium needed to be embedded in a material that was transparent to the light used to excite the nucleus. In this work, we showed that is simply not true,” said Hudson. “We can still force enough light into these opaque materials to excite nuclei near the surface, and then, instead of emitting photons like they do in transparent material such as the crystals, they emit electrons which can be detected simply by monitoring an electrical current — which is just about the easiest thing you can do in the lab!”

Thorium-based nuclear clocks could unlock satellite-free navigation

In addition to their expected impact on everything from communication technology, power grid synchronization and radar networks, next-generation clocks have long been sought as a solution to a problem with significant national security impact: navigating without GPS. If a bad actor — or even an electromagnetic storm — disabled enough satellites, all of our GPS navigation devices would fail. Similarly, submarines that dive deep in the ocean, where satellite signals cannot reach, already use atomic clocks for navigation, but current clocks are not accurate enough and after a few weeks, the submarines must surface to verify their location. In these demanding environments, the nuclear clock, which is better protected from its environment, excels over current atomic clocks.

“The UCLA team’s approach could help reduce the cost and complexity of future thorium‑based nuclear clocks,” said Makan Mohageg, optical clock lead at Boeing Technology Innovation. “Innovations like these may contribute to more compact, high‑stability timekeeping, relevant to several aerospace applications.”

And, if Earthlings ever want to travel into space, we need even more improved clocks for the same reason.

“The UCLA group led by Eric Hudson has done amazing work in teasing out a viable way to probe the nuclear transition in thorium — work extending over more than a decade. This work opens the way to a viable thorium clock,” said Eric Burt, who leads the High Performance Atomic Clock project at the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory and was not involved in the research. “In my opinion, thorium nuclear clocks could also revolutionize fundamental physics measurements that can be performed with clocks, such as tests of Einstein’s theory of relativity. Due to their inherent low sensitivity to environmental perturbations, future thorium clocks may also be useful in setting up a solar-system-wide time scale essential for establishing a permanent human presence on other planets.”

Reference: “Laser-based conversion electron Mössbauer spectroscopy of 229ThO2” by Ricky Elwell, James E. S. Terhune, Christian Schneider, Harry W. T. Morgan, Hoang Bao Tran Tan, Udeshika C. Perera, Daniel A. Rehn, Marisa C. Alfonso, Lars von der Wense, Benedict Seiferle, Kevin Scharl, Peter G. Thirolf, Andrei Derevianko and Eric R. Hudson, 10 December 2025, Nature.

DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-09776-4

The research was funded by the National Science Foundation and included physicists from the University of Manchester, University of Nevada Reno, Los Alamos National Laboratory, Ziegler Analytics, Johannes Gutenberg-Universität at Mainz, and Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München.

Leave a Reply