By Amit Malewar Published: December 5, 2025

Collected at: https://www.techexplorist.com/code-making-hard-produce-cu-64/101488/

In the hidden world of atoms, copper carries a quiet duality. Each atom contains 29 protons, but its neutrons can vary, and that variation makes all the difference. The most common naturally occurring variant, Cu‑63, with 34 neutrons, is stable and unremarkable. But add just one more neutron, and you get Cu‑64: a radioactive isotope with a half-life of about 13 hours.

That fleeting window is precisely what makes Cu‑64 so attractive for medicine. It lasts long enough to travel through the body to its target, yet decays quickly enough to minimize radiation exposure. The catch? Cu‑64 does not exist naturally. It must be forged.

Traditionally, Cu-64 is made in cyclotrons, large machines that speed up particles. The process is simple but expensive: take Ni-64, hit it with protons, and see the nickel nucleus absorb a proton, eject a neutron, and change into copper-64. It works well. But the method demands both a cyclotron and enriched Ni‑64, a rare isotope that drives up costs and limits accessibility.

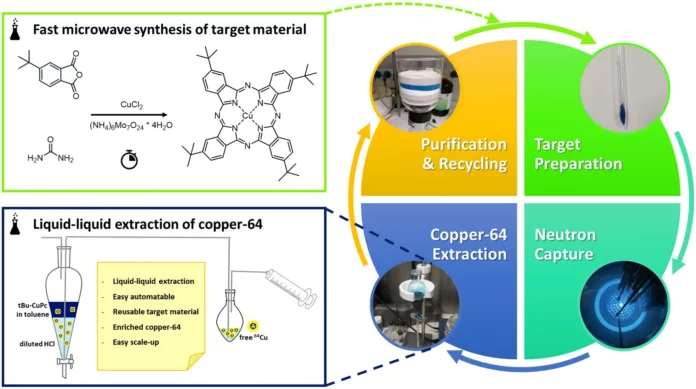

At TU Wien, researchers have now demonstrated a radically different pathway. Instead of cyclotrons, they turned to neutron irradiation in a research reactor, harnessing a century-old but underused phenomenon: recoil chemistry.

Before irradiation, copper atoms are embedded into specially designed molecules. Then comes the atomic drama.

“When a Cu‑63 atom within such a molecule absorbs a neutron and becomes Cu‑64, it briefly holds a large amount of excess energy, which it releases as gamma radiation,” says Veronika Rosecker.

That gamma emission acts like rocket exhaust. “The emission of this high-energy photon gives the atom a recoil, much like a rocket recoils when expelling exhaust. This recoil is strong enough to eject the copper atom from the molecule.”

And with that, the isotopes separate themselves. “This means that Cu‑63 and Cu‑64 can now be cleanly separated,” Rosecker explains. “The Cu‑63 atoms remain bound within the molecules, while the newly formed Cu‑64 atoms are released. This makes it easy to separate the two isotopes chemically.”

The challenge was finding a molecule tough enough to survive inside a nuclear reactor yet soluble enough for chemical processing afterward.

“We achieved this using a metal–organic complex that resembles heme, the molecule found in human blood,” explains Martin Pressler.

Earlier attempts with similar complexes failed due to insolubility. TU Wien’s team modified the chemistry to make the complex soluble, enabling straightforward recovery of Cu‑64 after irradiation.

The benefits are clear. The method can be automated, the molecules can be reused without losing quality, and it only requires a research reactor instead of a cyclotron. For hospitals and research centers, this could lead to cheaper and more accessible production of Cu‑64. This radioisotope is likely to become important in cancer diagnostics and targeted therapies.

In essence, TU Wien has turned a century-old curiosity into a modern medical tool. By giving copper atoms a rocket-like recoil, they’ve opened a new frontier in isotope production, one that could bring lifesaving treatments closer to patients worldwide.

Journal Reference:

- Martin Pressler, Christoph Denk, Hannes Mikula, and Veronika Rosecker. Fast and easy reactor-based production of copper-64 with high molar activities using recoil chemistry. Dalton Transactions. DOI: 10.1039/D5DT02046H

Leave a Reply