November 20, 2025 by Patricia Delacey, University of Michigan

Collected at: https://phys.org/news/2025-11-ai-turbulence-fresh-unsolved-physics.html

While atmospheric turbulence is a familiar culprit of rough flights, the chaotic movement of turbulent flows remains an unsolved problem in physics. To gain insight into the system, a team of researchers used explainable AI to pinpoint the most important regions in a turbulent flow, according to a Nature Communications study led by the University of Michigan and the Universitat Politècnica de València.

A clearer understanding of turbulence could improve forecasting, helping pilots navigate around turbulent areas to avoid passenger injuries or structural damage. It can also help engineers manipulate turbulence, dialing it up to help industrial mixing like water treatment or dialing it down to improve fuel efficiency in vehicles.

“For more than a century, turbulence research has struggled with equations too complex to solve, experiments too difficult to perform, and computers too weak to simulate reality. Artificial Intelligence has now given us a new tool to confront this challenge, leading to a breakthrough with profound practical implications,” said Sergio Hoyas, a professor of aerospace engineering at the Universitat Politècnica de València and co-author of the study.

When modeling turbulence, classical methods try to pick out the most influential elements using physical equations or by observing structures that can be easily seen in experiments, like vortices or eddies.

The new method shifts the focus from solely predicting turbulence to better understanding the system. It examines the entire flow without prior assumptions, removing each data point one by one to calculate its importance.

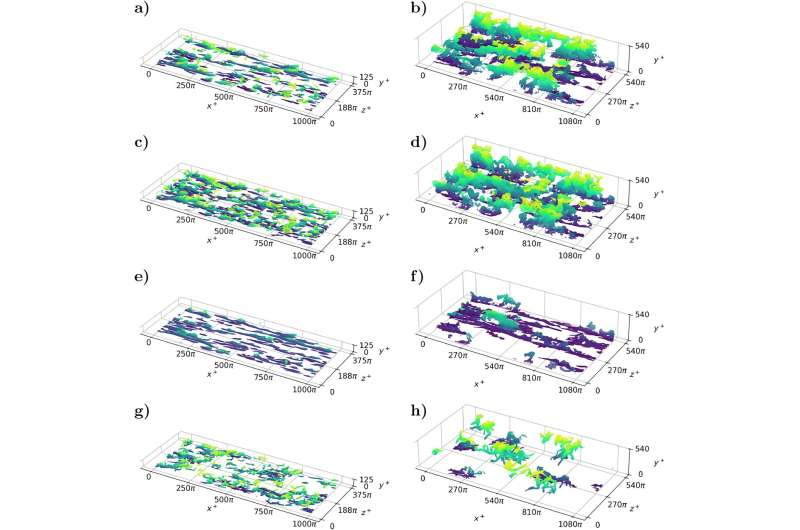

Contrary to classical assumptions, vortices had only a small importance far from the wall, the boundary between turbulent and smooth air. Instead, Reynolds stresses (the friction created when different speeds of fluids collide) were most influential very close and very far from the wall, while streaks (elongated ribbons of fast and slow moving air running parallel to the flow) held sway at moderate distances.

“If you put all the classical views together, they get closer to reconstructing the whole story. If you take each of the classical views individually, you get a partial story,” said Ricardo Vinuesa, an associate professor of aerospace engineering at U-M and co-corresponding author of the study.

An unsolved mathematical puzzle

Up to this point, researchers have been unable to fully understand how turbulent flows move or dissipate energy. The math to describe fluid motion comes from equations called the Navier-Stokes equations, which work well for smooth, predictable flows and mild turbulence.

For intense turbulence, i.e., almost every flow of practical interest, the equations are still valid, but require a huge amount of computational power to solve.

Turbulence is inherently chaotic, with velocity gradients that can become extremely large—approaching a near-singular behavior. In such conditions, the flow field exhibits a fractal-like structure, characterized by intricate and highly complex spatial configurations.

This complex behavior stems from the intricate interplay between the linear and nonlinear terms of the Navier–Stokes equations. It’s such a fundamental puzzle that the Clay Mathematics Institute named it one of seven Millenium Prize Problems, offering $1 million for a demonstration of the existence and uniqueness of a smooth solution of these equations.

Instantaneous visualization of the various coherent structures in the channel flow. Credit: Nature Communications (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-65199-9

A modeling workaround

While a computational technique called direct numerical simulation can model small pieces of turbulent flows with high accuracy, it’s prohibitively expensive to run on a larger scale.

Simulating one second of flight for an Airbus 320 in cruise conditions would take the world’s fastest supercomputer (with two exaflops of computing power) around five months. The memory required is similar to the amount of data transferred across the whole internet in one month.

As a workaround, the research team combined direct numerical simulation with explainable AI to gain new insights into turbulent flows. First, the research team used direct numerical simulation data to train an AI model to predict a turbulent flow. Then, they used Shapely additive explanations or SHAP to calculate the importance of each input of the first predictive AI model. This approach removes each input and measures how much it affects prediction accuracy.

“SHAP is like removing each player of a soccer team one by one to understand how each individual contributes to the team performance, helping to find the most valuable players,” said Vinuesa.

When put to the test, the SHAP method combined with deep reinforcement learning outcompeted classical approaches, reducing friction on an airplane wing by 30%. For the first time, we know exactly which structures are the most important in a turbulent flow.

“This means we can target these regions to develop control strategies that reduce drag, improve combustion, and decrease urban pollution more efficiently, as we can now anticipate the dynamics of the system,” said Andrés Cremades, an assistant professor at the Universitat Politècnica de València and co-corresponding author of the study.

The researchers note that this technique can be applied to problems beyond turbulence.

“For any physics problem, you can identify the features that are important and the ones that are not, and use that for optimization, control or other applications down the line,” adds Vinuesa.

More information: Andrés Cremades et al, Classically studied coherent structures only paint a partial picture of wall-bounded turbulence, Nature Communications (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-65199-9

Journal information: Nature Communications

Leave a Reply