By Penn State November 5, 2025

Collected at: https://scitechdaily.com/why-this-new-super-earth-has-scientists-so-excited-about-alien-life/

A giant exoplanet orbiting a nearby dwarf star has been found in an ideal location for next-generation telescopes to search for potential signs of life.

The discovery of a potential “super-Earth” located less than 20 light-years from Earth is giving scientists fresh optimism in their search for planets that could support life. The newly identified world, named GJ 251 c, has been classified as a “super-Earth” because observations suggest it is nearly four times more massive than our planet and is probably a rocky world.

“We look for these types of planets because they are our best chance at finding life elsewhere,” said Suvrath Mahadevan, the Verne M. Willaman Professor of Astronomy at Penn State and co-author on a paper about the discovery published in The Astronomical Journal. “The exoplanet is in the habitable or the ‘Goldilocks Zone,’ the right distance from its star that liquid water could exist on its surface, if it has the right atmosphere.”

For many years, astronomers have pursued planets that might sustain liquid water and potentially life. Their efforts have led to the creation of powerful telescopes and complex computer models capable of detecting even faint variations in starlight. According to Mahadevan, the identification of GJ 251 c is the product of more than twenty years of data collection and represents one of the most encouraging opportunities yet in the search for life beyond Earth.

Uncovering GJ 251 c

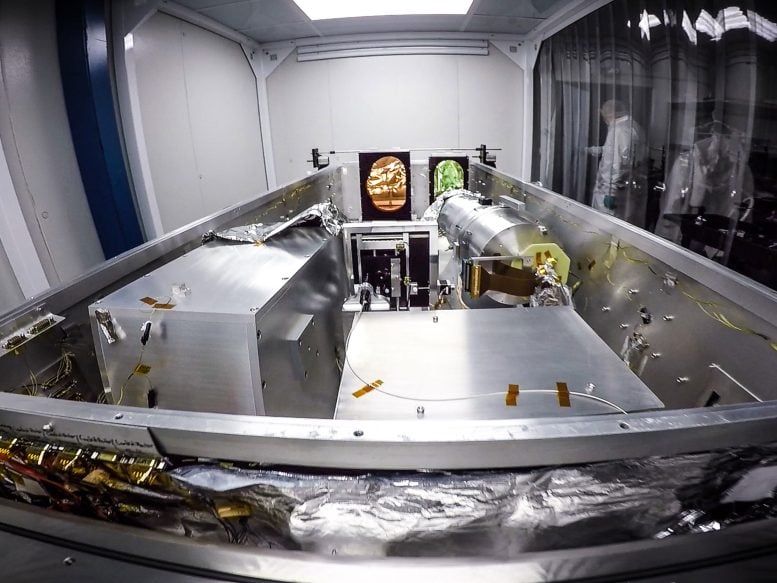

The exoplanet was identified through observations collected by the Habitable-Zone Planet Finder (HPF), a highly sensitive near-infrared spectrograph that functions like a sophisticated prism to separate and analyze light from stars. The instrument is installed on the Hobby-Eberly Telescope at the McDonald Observatory in Texas. Developed and constructed under the leadership of Penn State researchers, the HPF was specifically designed to locate Earth-like planets orbiting within the habitable zones of nearby stars.

“We call it the Habitable Zone Planet Finder, because we are looking for worlds that are at the right distance from their star that liquid water could exist on their surface. This has been the central goal of that survey,” Mahadevan said. “This discovery represents one of the best candidates in the search for atmospheric signature of life elsewhere in the next five to ten years.”

Mahadevan and his colleagues made the discovery by analyzing a vast collection of data, spanning over 20 years and collected by telescopes around the world, focusing on the slight movement, or “wobble,” of the planet’s host star, GJ 251. This “wobble” comprises tiny Doppler shifts in the star’s light caused by an orbiting planet’s gravity.

They used the baseline observations to first improve the “wobble” measurements of a previously known inner planet, GJ 251 b, which circles the star every 14 days. They then combined the baseline data with new high-precision data from the HPF to reveal a second, stronger signal at 54 days — indicating there was another, far more massive, planet in the system. The team further confirmed the planet’s signal using the NEID spectrometer built by Penn State researchers, which is attached to a telescope at the Kitt Peak National Observatory in Arizona.

“We are at the cutting edge of technology and analysis methods with this system,” said Corey Beard, corresponding author on the paper who conducted the research while earning a doctorate in astrophysics from the University of California, Irvine. “We need the next generation of telescopes to directly image this candidate, but what we also need is community investment.”

Overcoming Stellar “Noise”

One of the biggest challenges in finding distant worlds is disentangling the planetary signal from its star’s own activity, a kind of stellar weather, Mahadevan explained. Stellar activity, such as starspots, can mimic the periodic motion of a planet, giving the false impression of a planet where there is none. To distinguish signal from noise, the researchers applied advanced computational modeling techniques to analyze how signals change across different wavelengths, or colors, of light.

“This is a hard game in terms of trying to beat down stellar activity as well as measuring its subtle signals, teasing out slight signals from what is essentially this frothing, magnetospheric cauldron of a star surface,” Mahadevan said.

Looking Ahead

He explained that discovering exoplanets like GJ 251 c requires advanced instruments and complex data analysis. The work involves collaborations across multiple institutions and expertise throughout the world, and most importantly, requires a sustained commitment from the countries funding the research — which can often take decades to yield actionable results.

“This discovery is a great example of the power of multi-disciplinary research at Penn State,” said Eric Ford, distinguished professor astronomy and astrophysics and director of research for Penn State’s Institute of Computational & Data Sciences (ICDS). “Mitigating stellar activity noise required not just cutting-edge instrumentation and telescope access, but also customizing the data science methods for the specific needs of this star and combination of instruments. The combination of exquisite data and state-of-the-art statistical methods enabled our interdisciplinary team to transform data into an exciting discovery that paves the way for future observatories to search for evidence of life beyond our solar system.”

While the exoplanet that the team discovered is not possible to image with current instruments Mahadevan said, the next generation of telescopes would be able analyze the planet’s atmosphere, which could potentially reveal chemical signs of life.

“We are always focused on the future,” he said. “Whether that’s making sure the next generation of students can engage in cutting-edge research or designing and building new technology to detect potentially habitable planets.”

The newly found exoplanet is perfectly positioned for direct observation by more advanced technology. Mahadevan and his students are already planning for when more powerful telescopes, the new generation of 30-meter-class ground-based telescopes, comes online. Equipped with advanced instruments, the new telescopes are expected to have the capability to image nearby rocky planets in habitable zones.

“While we can’t yet confirm the presence of an atmosphere or life on GJ 251 c, the planet represents a promising target for future exploration,” Mahadevan said. “We made an exciting discovery, but there’s still much more to learn about this planet.”

Reference: “Discovery of a Nearby Habitable Zone Super-Earth Candidate Amenable to Direct Imaging” by Corey Beard, Paul Robertson, Jack Lubin, Eric B. Ford, Suvrath Mahadevan, Gudmundur Stefansson, Jason T. Wright, Eric Wolf, Vincent Kofman, Vidya Venkatesan, Ravi Kopparapu, Roan Arendtsz, Rae Holcomb, Raquel A. Martinez, Stephanie Sallum, Jacob K. Luhn, Chad F. Bender, Cullen H. Blake, William D. Cochran, Megan Delamer, Scott A. Diddams, Michael Endl, Samuel Halverson, Shubham Kanodia, Daniel M. Krolikowski, Andrea S. J. Lin, Sarah E. Logsdon, Michael W. McElwain, Andrew Monson, Joe P. Ninan, Jayadev Rajagopal, Arpita Roy, Christian Schwab and Ryan C. Terrien, 23 October 2025, The Astronomical Journal.

DOI: 10.3847/1538-3881/ae0e20

The U.S. National Science Foundation, NASA and the Heising-Simons Foundation supported the Penn State aspects of this research.

Leave a Reply