By Pranjal Malewar Published: September 4, 2025

Collected at: https://www.techexplorist.com/hidden-chemistry-earth-core/100880/

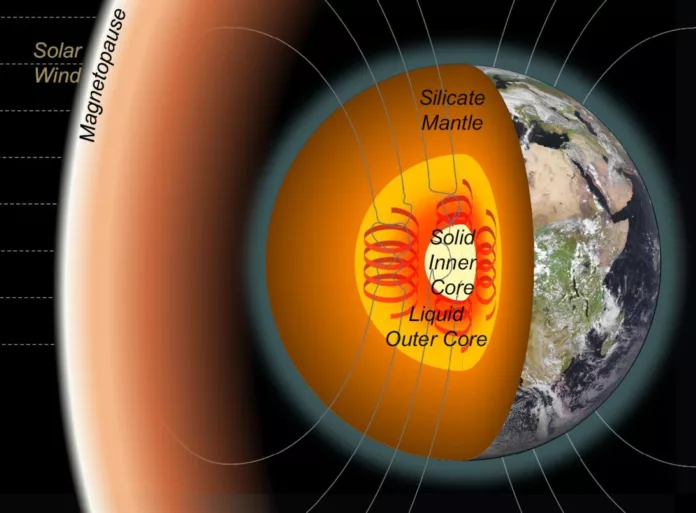

The composition of Earth’s core is a key factor in understanding the planet’s internal structure, as well as its long-term thermal and magnetic evolution. Despite its importance, the exact makeup of the core remains uncertain. Multiple combinations of light elements (such as sulfur, silicon, or oxygen) are consistent with existing constraints from cosmochemistry, core formation models, and seismic data.

Traditionally, it was assumed that the inner core forms when liquid metal freezes at its melting point. However, recent studies suggest that supercooling, where the liquid must cool below its melting point before solidifying, may be required. Calculations of the degree of supercooling needed show that several binary mixtures of core elements are incompatible with the conditions necessary for inner core nucleation.

Deep inside our planet, something remarkable happened millions of years ago: Earth’s molten core began to crystallize, forming the solid inner core we know today. But how did that freezing process even start?

A team of researchers from Oxford, Leeds, and UCL may have found a key clue. Their study suggests that for crystallization to begin, the core needed to contain at least 3.8% carbon, a surprisingly high amount.

Forming Earth’s inner core isn’t just about cooling; it’s about crystallizing, and that depends on the core’s chemistry. Like cloud droplets that need extra chill to become hail, molten iron must be supercooled before it can freeze.

If Earth’s core were pure iron, it would need to cool by a whopping 800–1,000°C to start freezing. But that much chill would’ve caused the inner core to balloon and the magnetic field to collapse, neither of which happened.

Instead, scientists think the core only cooled about 250°C below its melting point.

Scientists used computer simulations to study how Earth’s inner core formed with minimal cooling. They found that elements like silicon, sulfur, oxygen, and carbon may have helped the core solidify more easily.

“Each of these elements exists in the overlying mantle and could therefore have been dissolved into the core during Earth’s history,” explained co-author Associate Professor Andrew Walker (Department of Earth Sciences, University of Oxford).

“As a result, this could explain why we have a solid inner core with relatively little supercooling at this depth. The presence of one or more of these elements could also rationalize why the core is less dense than pure iron, a key observation from seismology.”

Using atomic-scale simulations, scientists observed the formation of tiny crystal clusters and early signs of freezing under core-like conditions. Surprisingly, silicon and sulfur slowed the process, meaning Earth’s core would need to be colder to start freezing if these elements were common. But carbon accelerated the process, making freezing easier.

The team tested how much cooling the core would need to start freezing if it contained carbon. With 2.4% carbon, it required a steep 420°C drop, which was still too much. But when they bumped it to 3.8%, the required cooling dropped to 266°C, making it the only known mix that fits both how the inner core formed and its current size.

The takeaway? Carbon might be far more abundant in Earth’s core than we thought, and without it, our solid inner core may never have formed at all.

Unlike hailstones that need tiny particles to kickstart freezing, Earth’s inner core may have solidified without any nucleation seeds. These new experiments suggest that with just the right carbon-rich chemistry, the core didn’t need a trigger; it froze spontaneously.

Lead author Dr. Alfred Wilson (School of Earth and Environment, University of Leeds) said, “It is exciting to see how atomic-scale processes control the fundamental structure and dynamics of our planet. By studying how Earth’s inner core formed, we are not just learning about our planet’s past. We’re getting a rare glimpse into the chemistry of a region we can never hope to reach directly and learning about how it could change in the future.”

Journal Reference:

- Constraining Earth’s core composition from inner core nucleation, Nature Communications (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-62841-4

Leave a Reply