By Space Telescope Science Institute June 15, 2025

Collected at: https://scitechdaily.com/hubbles-dusty-surprise-why-uranus-moons-are-darker-on-the-wrong-side/

New surface data from largest Uranian moons are contrary to expectations.

Astronomers using NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope set out to study how Uranus’ magnetic environment might be affecting its four largest moons. They expected to find one thing, but what they discovered was something entirely different. Thanks to Hubble’s powerful and precise observations, the team uncovered a surprising new clue that could change how we understand these distant, icy worlds.

Moons of Uranus Surprise Scientists in NASA Hubble Study

Scientists using NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope set out to investigate how Uranus’ powerful magnetic field might be affecting its largest moons, but what they discovered was completely unexpected.

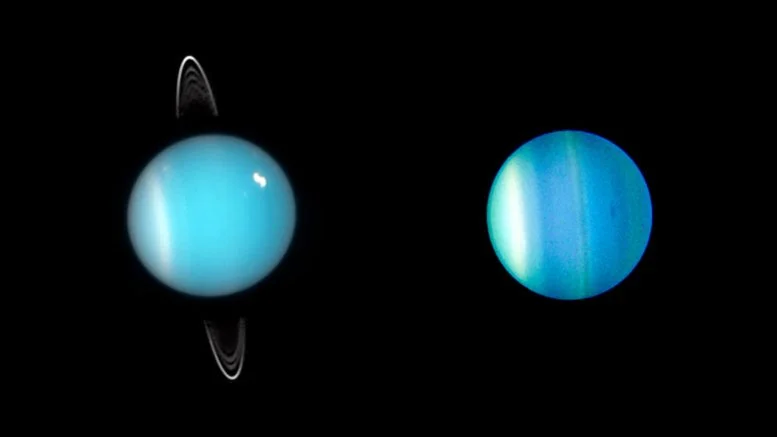

The team focused on the four biggest moons of Uranus, the icy blue planet that orbits seventh from the Sun. They were looking for signs that Uranus’ magnetosphere—a magnetic bubble filled with charged particles—was interacting with the moons’ surfaces.

They predicted that radiation from the magnetosphere would darken the “trailing” sides of the moons, which always face away from their direction of orbit. The “leading” sides, facing forward, were expected to be brighter.

A Surprising Surface Pattern Emerges

But the data told a different story. Hubble found no darkening on the trailing sides. Instead, the outer moons had darker leading sides—a complete reversal of what scientists expected. This surprising result suggests that Uranus’ magnetosphere may not be interacting with its moons in the way previously thought, challenging earlier findings based on infrared observations.

Hubble’s sharp ultraviolet vision and spectroscopic capabilities made this discovery possible, revealing details on the moons’ surfaces that no other telescope could detect.

Decoding a Mysterious Magnetosphere

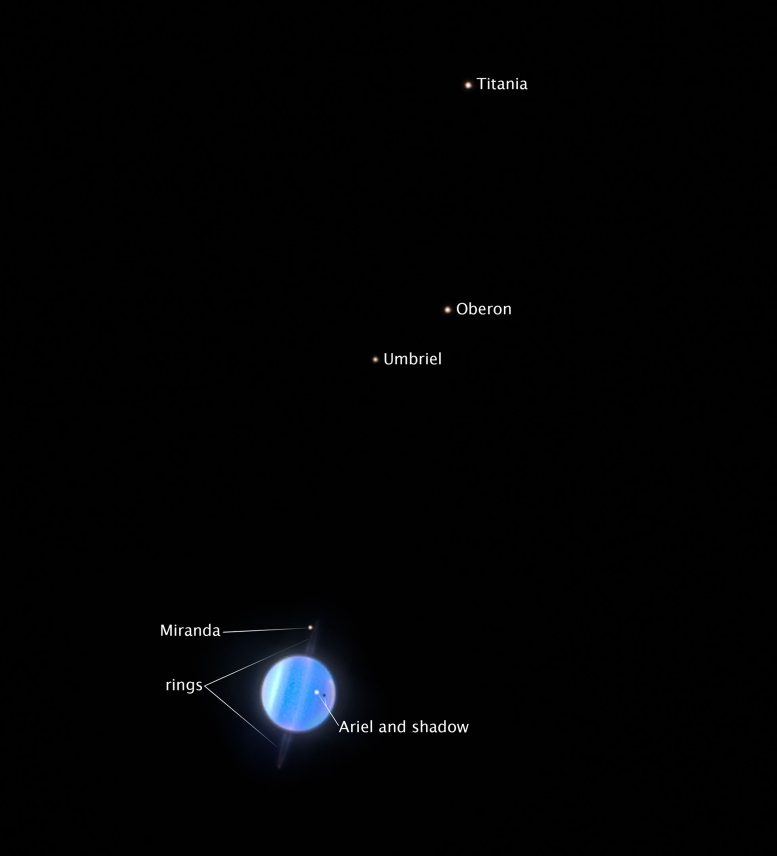

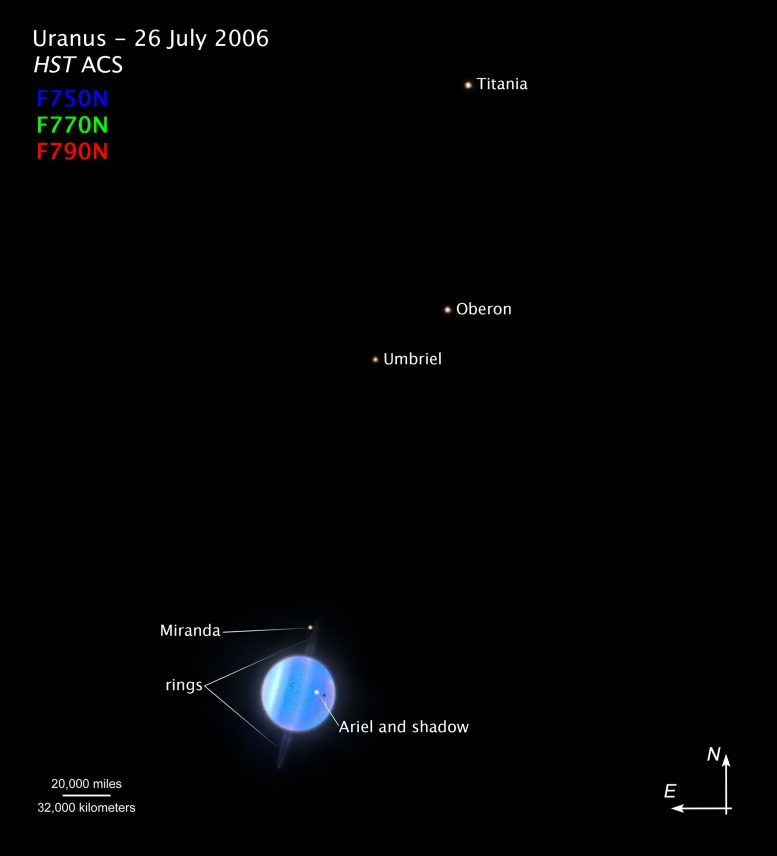

The four moons in this study — Ariel, Umbriel, Titania, and Oberon — are tidally locked to Uranus, so that they always show the same side to the planet. The side of the moon facing the direction of travel is called the leading hemisphere, while the side that faces backward is called the trailing hemisphere. The thinking was that charged particles trapped along the magnetic field lines primarily hit each moon’s trailing side, which would darken that hemisphere.

The image shows a scale bar, compass arrows, and color key for reference.

The scale bar is labeled in miles along the top and kilometers along the bottom.

The north and east compass arrows show the orientation of the image on the sky. Note that the relationship between north and east on the sky (as seen from below) is flipped relative to direction arrows on a map of the ground (as seen from above).

This image shows visible wavelengths of light that have been translated into visible-light colors. The color key shows which ACS filters were used when collecting the light. The color of each filter name is the visible-light color used to represent the light that passes through that filter.

Credit: NASA, ESA, STScI, Christian Soto (STScI)

A Tilted Planet With a Twisted Field

“Uranus is weird, so it’s always been uncertain how much the magnetic field actually interacts with its satellites,” explained principal investigator Richard Cartwright of the Johns Hopkins University’s Applied Physics Laboratory. “For starters, it is tilted by 98 degrees relative to the ecliptic.”

This means Uranus is dramatically tipped relative to the orbital plane of the planets. It rolls very slowly around the Sun on its side as it completes its 84-Earth-year orbit.

“At the time of the Voyager 2 flyby, the magnetosphere of Uranus was tilted by about 59 degrees from the orbital plane of the satellites. So, there’s an additional tilt to the magnetic field,” explained Cartwright.

High-Speed Field Sweeps and Cosmic Darkening

Because Uranus and its magnetic field lines rotate faster than its moons orbit the planet, the magnetic field lines constantly sweep past the moons. If the magnetosphere of Uranus interacts with its moons, charged particles should preferentially hit the surface of the trailing sides.

These charged particles, as well as our galaxy’s cosmic rays, should darken the trailing hemispheres of Ariel, Umbriel, Titania, and Oberon and possibly generate the carbon dioxide detected on these moons. The team expected that, especially for the inner moons Ariel and Umbriel, the trailing hemispheres would be darker than the leading sides in ultraviolet and visible wavelengths.

But that’s not what they found. Instead, the leading and trailing hemispheres of Ariel and Umbriel are actually very similar in brightness. However, the researchers did see a difference between the hemispheres of the two outer moons, Titania and Oberon — not the moons they expected.

Cosmic Dust and Collision Theory

Even stranger, the difference in brightness was the opposite of what they expected. The two outer moons have darker and redder leading hemispheres compared with their trailing hemispheres. The team thinks that dust from some of Uranus’ irregular satellites is coating the leading sides of Titania and Oberon.

Irregular satellites are natural bodies that have large, eccentric, and inclined orbits relative to their parent planet’s equatorial plane. Micrometeorites are constantly hitting the surfaces of Uranus’ irregular satellites, ejecting small bits of material into orbit around the planet.

Over millions of years, this dusty material moves inward toward Uranus and eventually crosses the orbits of Titania and Oberon. These outer moons sweep through the dust and pick it up primarily on their leading hemispheres, which face forward. It’s much like bugs hitting the windshield of your car as you drive down a highway.

Inner Moons Get a Protective Shield

This material causes Titania and Oberon to have darker and redder leading hemispheres. These outer moons effectively shield the inner moons Ariel and Umbriel from the dust, which is why the inner moons’ hemispheres do not show a difference in brightness.

“We see the same thing happening in the Saturn system and probably the Jupiter system as well,” said co-investigator Bryan Holler of the Space Telescope Science Institute. “This is some of the first evidence we’re seeing of a similar material exchange among the Uranian satellites.”

“So that supports a different explanation,” said Cartwright. “That’s dust collection. I didn’t even expect to get into that hypothesis, but you know, data always surprise you.”

Based on these findings, Cartwright and his team suspect that Uranus’ magnetosphere may be fairly quiescent, or it may be more complicated than previously thought. Perhaps interactions between Uranus’ moons and magnetosphere are happening, but for some reason, they’re not causing asymmetry in the leading and trailing hemispheres as researchers suspected. The answer will require further investigation into enigmatic Uranus, its magnetosphere, and its moons.

Hubble’s Ultraviolet Superpower

To observe the brightnesses of the four largest Uranian moons, the researchers required Hubble’s unique ultraviolet capabilities. Observing targets in ultraviolet light is not possible from the ground because of the filtering effects of Earth’s protective atmosphere. No other present-day space telescopes have comparable ultraviolet vision and sharpness.

“Hubble, with its ultraviolet capabilities, is the only facility that could test our hypothesis,” said the Space Telescope Science Institute’s Christian Soto, who conducted much of the data extraction and analysis. Soto presented results from this study on June 10 at the 246th Meeting of American Astronomical Society in Anchorage, Alaska.

Complementary data from NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope will help to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the Uranian satellite system and its interactions with the planet’s magnetosphere.

The Hubble Space Telescope is one of the most iconic and productive observatories in human history, operating for over three decades and continually transforming our understanding of the cosmos. Launched in 1990, Hubble has made groundbreaking discoveries across nearly every field of astronomy—from revealing the expansion rate of the universe to capturing breathtaking images of distant galaxies, nebulae, and exoplanets.

Hubble is a flagship project of international collaboration between NASA and the European Space Agency (ESA). It is managed by NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, with Lockheed Martin Space in Denver supporting mission operations. The Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, operated by the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy (AURA), oversees the telescope’s scientific activities, supporting researchers worldwide in unlocking the secrets of space.

Despite its age, Hubble remains a critical scientific asset, delivering high-resolution ultraviolet, visible, and near-infrared observations that ground-based telescopes cannot match due to Earth’s atmospheric interference. Its enduring legacy is not just its data, but the profound impact it continues to have on space science and public imagination.

The Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) is a premier hub for space astronomy, dedicated to expanding our understanding of the universe through the operation of some of NASA’s most important observatories. Located in Baltimore, Maryland, STScI serves as the science operations center for the Hubble Space Telescope, the science and mission operations center for the James Webb Space Telescope, and the science operations center for the upcoming Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope.

In addition to overseeing mission science, STScI also manages the Barbara A. Mikulski Archive for Space Telescopes (MAST)—a NASA-funded archive that provides the global astronomy community with access to a vast array of space-based data. MAST is the official data repository for key missions such as Hubble, Webb, Roman, Kepler, K2, and TESS, among others.

Operated by the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy (AURA), STScI plays a vital role in supporting astronomical discovery, mission planning, data analysis, and community engagement, serving as the scientific engine behind some of humanity’s most powerful space telescopes.

Leave a Reply