By Kenna Hughes-Castleberry, JILA February 21, 2025

Collected at: https://scitechdaily.com/quantum-billiards-cracking-the-code-of-light-assisted-atomic-collisions/

In a groundbreaking study, scientists developed new ways to control atom collisions using optical tweezers, offering insights that could advance quantum computing and molecular science.

By manipulating light frequencies and atomic energy levels, they mapped out how specific atomic characteristics influence collision outcomes, paving the way for more precise quantum manipulation.

Quantum Surprises at Ultra-Cold Temperatures

When atoms collide, their structure—such as the number of electrons they carry or the quantum spin of their nuclei—determines how they interact. This effect becomes even more pronounced at ultra-cold temperatures near absolute zero, where quantum mechanics plays a dominant role. In these extreme conditions, atoms can sometimes collide due to laser light, briefly forming a molecular state before breaking apart and releasing a significant burst of energy. These light-assisted collisions happen rapidly and influence a wide range of quantum science applications, yet the details of how they occur remain poorly understood.

In a new study published in Physical Review Letters, JILA Fellow and University of Colorado Boulder physics professor Cindy Regal, along with former JILA Associate Fellow Jose D’Incao (now at the University of Massachusetts, Boston), and their teams developed innovative experimental and theoretical methods to measure the rates of light-assisted collisions in the presence of small atomic energy splittings. Their research relies on optical tweezers—highly focused laser beams that can trap individual atoms—allowing the team to isolate and examine the interactions of specific atom pairs with unprecedented precision.

By uncovering new insights into these specialized atomic collisions, the researchers are helping to improve control over atomic interactions, a crucial step for advancing quantum simulations that use arrays of atoms and molecules to model complex quantum systems.

Advancements in Optical Tweezer Research

As physicists work to improve control over atoms in optical tweezer experiments, JILA graduate student Steven Pampel, the paper’s first author, wanted to better understand how the rate at which light-assisted collisions occur changes under a range of circumstances. Light can create a wild array of outcomes, depending mostly on its frequency with respect to atomic transitions.

“Light-assisted collisions can generate large amounts of energy compared to what is often tolerated in the world of ultracold atomic gases,” Regal elaborates. “This energy is imparted to the colliding atoms, which can be considered bad as they are large enough to cause atoms to escape from typical traps. But these collisions can also be useful when that energy can be controlled.”

In fact, the Regal group and other groups worldwide have previously used this energy to study how to load atoms into optical tweezers. However, a more comprehensive theoretical understanding of the collision process leading to such energy release was hard to come by, especially when considering atomic hyperfine structure—small energy shifts resulting from the coupling between an atom’s nuclear spin and angular momentum from the atom’s electrons.

The basic model for light-assisted collisions has been understood for decades. In fact, the go-to model was developed by JILA Fellow Allan Gallagher and collaborator Prof. David Pritchard of MIT. But until recently, our understanding of light-assisted collisions came from very large optical traps that contain millions of atoms where the same light that confines the atoms also drives collisions, limiting control over the frequency of the light and information someone could obtain.

Precise Manipulation of Quantum States

To determine how fast the collisions occur, the researchers in Regal’s laboratory began their experiment by preparing exactly two rubidium atoms in an optical tweezer. To accomplish this, the team harnessed a technique where single atoms are loaded into two separate optical tweezers and then the atoms are merged into a single optical trap. After merging, a carefully controlled pulse of laser light was applied to drive collisions between the two atoms.

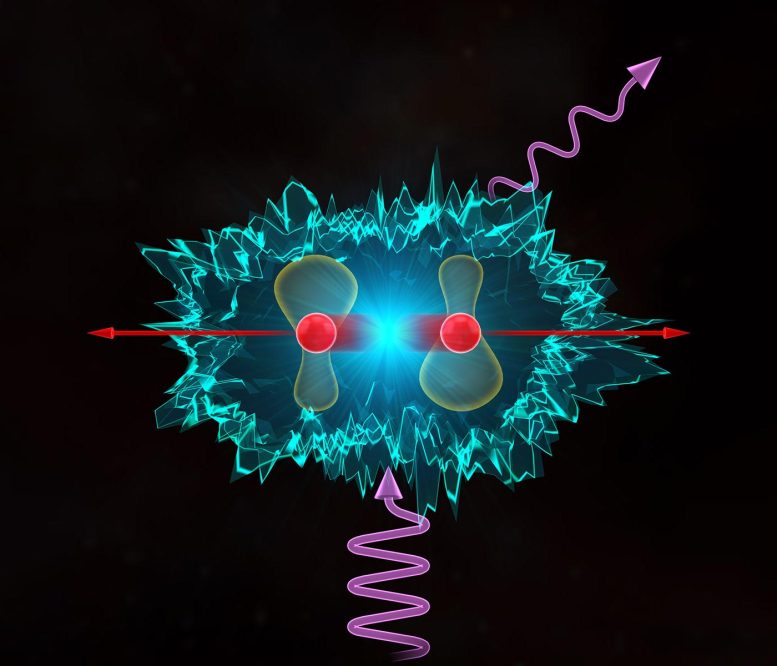

This collisional laser light excites the atoms, creating a quantum superposition state where either atom could have absorbed a photon, but it is unclear which one. In this state, electronic forces act at much larger distances than they otherwise would and give the atoms such a large amount of kinetic energy that they escape the trap. In this game of “quantum billiard balls,” the photon is like the cue ball that smashes into two other balls (the atoms) simultaneously, sending them flying off the table.

The team then varied the frequency of the collisional light, i.e., the energy of the photon “cue,” and measured how quickly atom-pairs escaped the optical tweezer.

“We set the laser at a certain frequency, then varied the duration of the collisional light to see how many atoms remained in the trap,” Pampel adds. “From this, we could determine how quickly the atoms collided and gained enough energy to escape. By repeating this process at different frequencies, we could map out the influence of hyperfine structure in these collisions.”

This process allowed the researchers to measure the loss rates of the atoms quantitatively and in relation to the hyperfine effects, something that had never been done before.

Breakthrough in Collision Imaging Techniques

During the experiments, the team developed a novel imaging technique to accurately determine if both atoms remained in the trap after a collision. This technique was crucial because standard imaging methods in optical tweezers would inadvertently kick both atoms out of the trap during the collision, making it impossible to tell whether the collisional light or the imaging light kicked out the atoms.

“We came up with a method that uses a special type of light-assisted collisions where only one atom gets kicked out most of the time,” Pampel explains. “This allowed us to identify the presence of two atoms by detecting a single atom. This mechanism is commonly used for loading single atoms in tweezers, but we showed it can be used in a more controlled setting for two-atom detection purposes as well.”

The researchers also developed a theoretical model to understand their experimental results, particularly why setting the light frequency to be close to that of certain hyperfine states resulted in different rates than other hyperfine states.

“Mapping out the potential energy curves for two colliding atoms in the presence of light and the hyperfine interaction required more complex analysis than previous works that had only taken into account the atomic fine structure—the interaction between electron’s spin and angular momentum,” D’Incao says.

“In addition, we built a collisional model that allows us to gain a better understanding of how the many hyperfine-dependent molecular states give rise to collision rates and the amount of energy released,” Pampel adds. This model could also be extended beyond rubidium atoms, helping to predict how other atomic elements might behave in similar situations.

Insights into Quantum Interactions and Future Applications

Beyond shedding new light on a long-standing puzzle, these findings could influence various endeavors with trapped neutral atoms such as quantum computing, metrology, and many-body physics, where controlling atomic collisions is essential for success. The ability to predict how atomic collisions will behave based on their hyperfine structure will likely be useful for advancing laser-cooling techniques, molecular quantum science, and the next generation of quantum-based technologies.

Reference: “Quantifying Light-Assisted Collisions in Optical Tweezers across the Hyperfine Spectrum” by Steven K. Pampel, Matteo Marinelli, Mark O. Brown, José P. D’Incao and Cindy A. Regal, 10 January 2025, Physical Review Letters.

DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.134.013202

This research was supported by the Office of Naval Research, the National Science Foundation, the Department of Energy, the Quantum Systems Accelerator and the Swiss National Science Foundation.

Leave a Reply