By Iqbal Pittalwala, University of California – Riverside February 19, 2025

Collected at: https://scitechdaily.com/this-gravitational-wave-breakthrough-could-rewrite-what-we-know-about-the-universe/

A new adaptive optics technology is set to transform gravitational-wave detection, allowing LIGO and future observatories like Cosmic Explorer to reach new heights.

By correcting mirror distortions, this breakthrough will enable extreme laser power levels, helping scientists explore the universe’s earliest moments and refine our understanding of black holes and spacetime.

Expanding the Reach of Gravitational-Wave Observatories

A recent study published in Physical Review Letters presents a breakthrough in optical technology that could significantly enhance the reach of gravitational-wave observatories like LIGO (Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory). Led by Jonathan Richardson of the University of California, Riverside, the research demonstrates how this advancement could not only improve current detection capabilities but also lay the foundation for next-generation observatories.

Since its first detection in 2015, LIGO has revolutionized our ability to observe the universe. Future upgrades to its 4-kilometer detectors, along with the planned construction of the 40-kilometer Cosmic Explorer, aim to extend gravitational-wave detection to the earliest moments in cosmic history—before the first stars even formed. However, achieving this goal requires pushing laser power levels beyond 1 megawatt, far exceeding LIGO’s current capabilities.

The study introduces a new low-noise, high-resolution adaptive optics system designed to overcome this limitation. This technology corrects distortions in LIGO’s massive 40-kilogram mirrors, which occur as laser power increases and heats the system. By enabling extreme laser power levels, this breakthrough could dramatically expand the sensitivity of gravitational-wave detectors, bringing us closer to unlocking the universe’s most distant and elusive signals.

Richardson, an assistant professor of physics and astronomy, explains the paper’s findings in the following Q&A:

What are gravitational waves?

Gravitational waves are a new way to observe the universe. They are predicted by the equations of general relativity. When massive objects accelerate or collide in the universe, distortions in the fabric of space-time propagate out like ripples in a pond at the speed of light. These distortions are gravitational waves and, like electromagnetic waves, they carry energy and momentum. We now have a lot of information about the extreme astrophysical objects like black holes that create them and about the physics of the underlying nature of spacetime that these waves travel through to reach us.

How does LIGO work?

LIGO is one of the largest pieces of scientific equipment in the world. It consists of two 4-kilometer by 4-kilometer long laser interferometers. One of these interferometers is in inland Washington State; the other is outside Baton Rouge, Louisiana. These sister sites operate in tandem, passively listening to any distortions of spacetime that might happen to propagate through Earth as a gravitational wave.

LIGO so far has seen about 200 events of stellar mass compact objects colliding and merging with each other. The overwhelming majority have been mergers of two black holes, but we’ve also seen mergers of neutron stars. I hope we may one day detect some source that is completely unexpected and unpredicted. If you look at the history of astronomy, every time we’ve developed electromagnetic telescopes that can observe a different wavelength of light than has never been observed before, we see the universe literally in a new light and have almost always discovered new types of objects visible in that wavelength band but not in others. I hope the same is true for gravitational waves.

Tell us about the instrument you’ve developed in your lab that has LIGO applications.

My focus at UCR is on developing new types of laser adaptive optical technology to overcome very fundamental physics limitations to how sensitive we can make detectors like LIGO. Across the majority of gravitational wave signal frequencies we can see from the ground, almost all of them are limited in sensitivity by quantum mechanics, by the quantum properties of the laser light itself that we use in the interferometer to bounce off mirrors. The instrument we’ve developed in my lab is designed to deliver precision optical corrections directly to the main mirrors of the LIGO interferometers. Our instrument is designed to sit just centimeters in front of the reflective surface of these mirrors and project very low noise corrective infrared radiation onto the front surface of the mirror. It is the first prototype for a totally new type of approach that uses non-imaging optical principles, which has never been used in gravitational wave detection before.

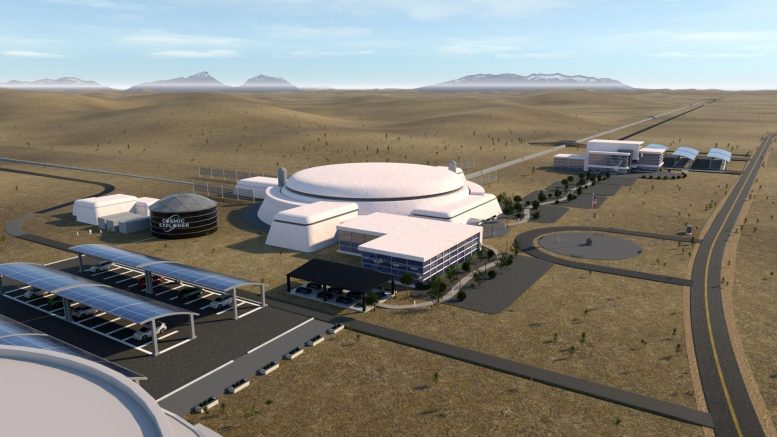

What is Cosmic Explorer?

Cosmic Explorer is the U.S. concept for a next-generation gravitational-wave observatory, after LIGO. It will be 10 times the size of LIGO, so that’s 40 by 40-kilometer-long interferometer arms. It will be the largest scientific instrument ever built. At their design sensitivity, these detectors will see the universe at earlier times than when the first stars are believed to have formed, when the universe was about 0.1% of its present 14-billion-year age. We will be able to see a snapshot of the universe at a very early stage in time.

Briefly, what does the research paper discuss?

The paper demonstrates that high-precision optical corrections are essential to expanding our gravitational-wave view of the universe. It lays out the potential implications for the impact we expect our new technology to have in the next generation of LIGO and in the years beyond that. Importantly, the paper shows that this type of technology is necessary and adequate to enable much higher levels of circulating laser power in the LIGO detectors than ever before. We expect this technology, and future versions of it, will be able to achieve more power in the interferometer.

Why is it important to do this research?

This research promises to answer some of the deepest questions in physics and cosmology, such as how fast the universe is expanding and the true nature of black holes. There are two contradicting measures right now of the local expansion rate of the universe, which gravitational waves can potentially resolve. Gravitational waves will also provide exquisitely high precision measurements of the detailed dynamics around the event horizons of black holes, allowing us to make direct tests of classical general relativity and alternative theories.

Reference: “Expanding the Quantum-Limited Gravitational-Wave Detection Horizon” by Liu Tao, Mohak Bhattacharya, Peter Carney, Luis Martin Gutierrez, Luke Johnson, Shane Levin, Cynthia Liang, Xuesi Ma, Michael Padilla, Tyler Rosauer, Aiden Wilkin and Jonathan W. Richardson, 5 February 2025, Physical Review Letters.

DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.134.051401

Leave a Reply