By Kimm Fesenmaier, California Institute of Technology February 9, 2025

Collected at: https://scitechdaily.com/from-sci-fi-to-reality-laser-powered-sails-are-changing-the-future-of-space-travel/

Caltech scientists are developing laser-driven lightsails that could push spacecraft beyond our solar system. Their research focuses on understanding how ultrathin materials respond to radiation pressure, a critical step toward creating stable, high-speed space probes.

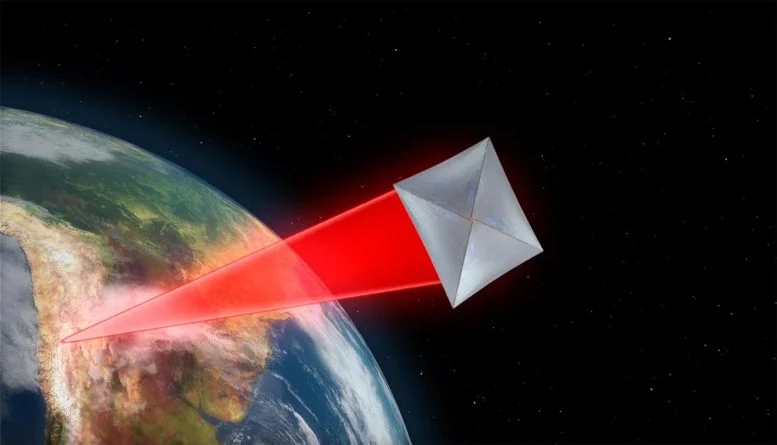

The idea of using ultrathin sails to travel through interstellar space might sound like science fiction, but it’s a real concept being explored by scientists. In 2016, physicist Stephen Hawking and entrepreneur Yuri Milner launched the Breakthrough Starshot Initiative, a program designed to study how laser-powered “lightsails” could propel tiny space probes at extreme speeds. The ultimate goal is to send these probes to Alpha Centauri, our nearest star system.

Caltech is at the forefront of this ambitious effort, leading a global research community working to make lightsail technology a reality. “The lightsail will travel faster than any previous spacecraft, with potential to eventually open interstellar distances to direct spacecraft exploration that are now only accessible by remote observation,” explains Harry Atwater, the Otis Booth Leadership Chair of the Division of Engineering and Applied Science and the Howard Hughes Professor of Applied Physics and Materials Science at Caltech.

Testing the Future of Lightsails

Now, Atwater and his colleagues at Caltech have developed a platform for characterizing the ultrathin membranes that could one day be used to make these lightsails. Their test platform includes a way to measure the force that lasers exert on the sails and that will be used to send the spacecraft hurtling through space. The team’s experiments mark the first step in moving from theoretical proposals and designs of lightsails to actual observations and measurements of the key concepts and potential materials.

“There are numerous challenges involved in developing a membrane that could ultimately be used as lightsail. It needs to withstand heat, hold its shape under pressure, and ride stably along the axis of a laser beam,” Atwater says. “But before we can begin building such a sail, we need to understand how the materials respond to radiation pressure from lasers. We wanted to know if we could determine the force being exerted on a membrane just by measuring its movements. It turns out we can.”

A Major Step Toward Practical Implementation

A paper describing the work was published on January 30 in the journal Nature Photonics. The lead authors of the paper are postdoctoral scholar in applied physics Lior Michaeli and graduate student in applied physics Ramon Gao (MS ’21), both of Caltech.

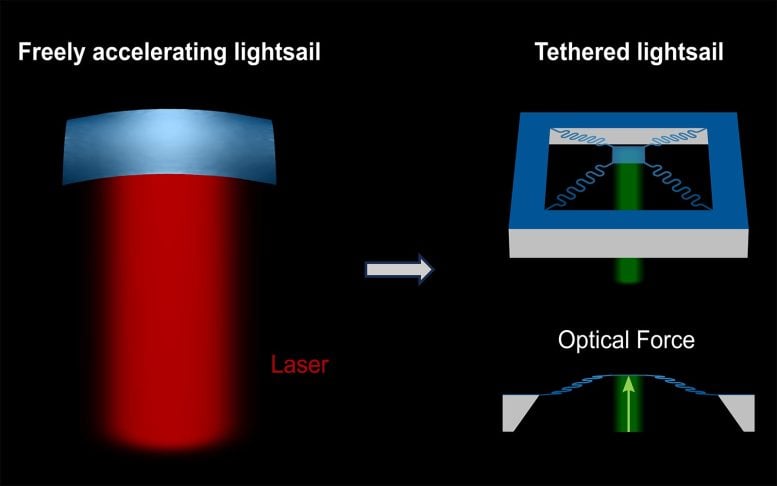

The goal is to characterize the behavior of a freely moving lightsail. But as a first step, to begin studying the materials and propulsive forces in the lab, the team created a miniature lightsail that is tethered at the corners within a larger membrane.

Using Nanotechnology to Build a Better Lightsail

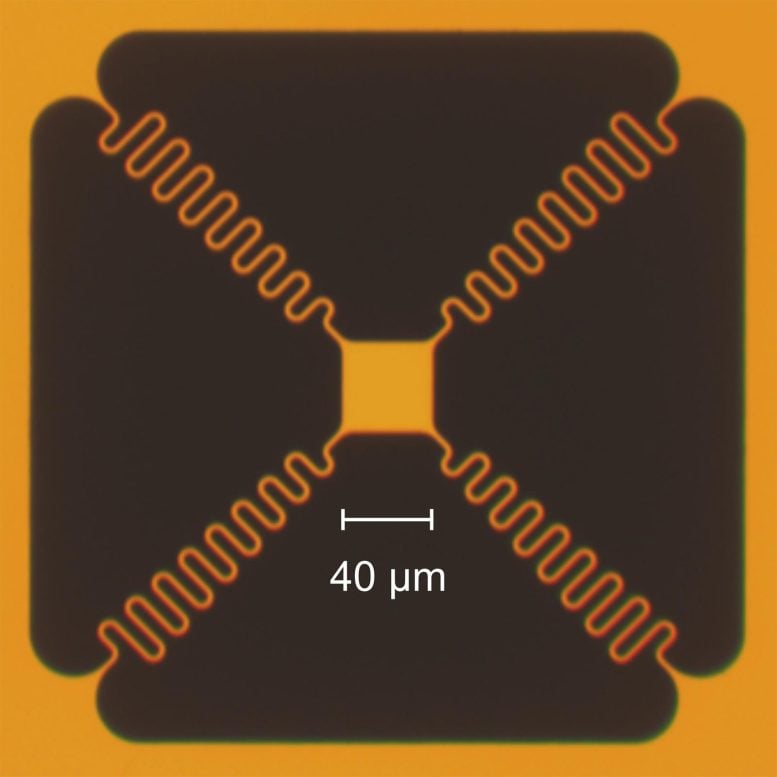

The researchers used equipment in the Kavli Nanoscience Institute at Caltech and a technique called electron beam lithography to carefully pattern a membrane of silicon nitride just 50 nanometers thick, creating something that looks like a microscopic trampoline. The mini trampoline, a square just 40 microns wide and 40 microns long, is suspended at the corners by silicon nitride springs. Then the team hit the membrane with argon laser light at a visible wavelength. The goal was to measure the radiation pressure that the miniature lightsail experienced by measuring the trampoline’s motions as it moved up and down.

But the picture from a physics perspective changes when the sail is tethered, says co-lead author Michaeli. “In this case, the dynamics become quite complex.” The sail acts as a mechanical resonator, vibrating like a trampoline when hit by light. A key challenge is that these vibrations are mainly driven by heat from the laser beam, which can mask the direct effect of radiation pressure. Michaeli says the team turned this challenge into an advantage. “We not only avoided the unwanted heating effects but also used what we learned about the device’s behavior to create a new way to measure light’s force.”

A Breakthrough in Measuring Light’s Force

The new method lets the device act additionally as a power meter to measure both the force and power of the laser beam.

“The device represents a small lightsail, but a big part of our work was devising and realizing a scheme to precisely measure motion induced by long-range optical forces,” says co-lead author Gao.

To do that, the team built what is called a common-path interferometer. In general, motion can be detected by the interference of two laser beams, where one hits the vibrating sample and the other traces a rigid location. However, in a common-path interferometer, because the two beams have traveled nearly the same path, they have encountered the same sources of environmental noise, such as equipment operating nearby or even people talking, and those signals get eliminated. All that remains is the very small signal from the motion of the sample.

The engineers integrated the interferometer into the microscope they used to study the miniature sail and housed the device within a custom-made vacuum chamber. They were then able to measure motions of the sail as small as picometers (trillionths of a meter) as well as its mechanical stiffness—that is, how much the springs deformed when the sail was pushed by the laser’s radiation pressure.

Testing Realistic Spaceflight Conditions

Since the researchers know that a lightsail in space would not always remain perpendicular to a laser source on Earth, they next angled the laser beam to mimic this and again measured the force with which the laser pushed the mini sail. Importantly, the researchers accounted for the laser beam spreading out at an angle and therefore missing the sample in some areas by calibrating their results to the laser power measured by the device itself. Yet, the force under those circumstances was lower than expected. In the paper, the researchers hypothesize that some of the beam, when directed at an angle, hits the edge of the sail, causing a portion of the light to get scattered and sent in other directions.

Engineering the Future of Interstellar Propulsion

Looking forward, the team hopes to use nanoscience and metamaterials—materials carefully engineered at that tiny scale to have desirable properties—to help control the side-to-side motion and rotation of a miniature lightsail.

“The goal then would be to see if we can use these nanostructured surfaces to, for example, impart a restoring force or torque to a lightsail,” says Gao. “If a lightsail were to move or rotate out of the laser beam, we would like it to move or rotate back on its own.”

The researchers note that they can measure side-to-side motion and rotation with the platform described in the paper. “This is an important stepping stone toward observing optical forces and torques designed to let a freely accelerating lightsail ride the laser beam,” says Gao.

Reference: “Direct radiation pressure measurements for lightsail membranes” by Lior Michaeli, Ramon Gao, Michael D. Kelzenberg, Claudio U. Hail, Adrien Merkt, John E. Sader and Harry A. Atwater, 30 January 2025, Nature Photonics.

DOI: 10.1038/s41566-024-01605-w

Along with Atwater, Michaeli, and Gao, additional Caltech authors on the paper are senior research scientist Michael D. Kelzenberg (PhD ’10), former postdoctoral scholar Claudio U. Hail, and research professor John E. Sader. Adrien Merkt is also an author of the paper who participated in the project as a graduate student at ETH Zürich. The work was supported by the Air Force Office of Scientific Research and the Breakthrough Starshot Initiative.

Leave a Reply